A quack! Fraud! Anti-science! Dangerous!

I was quite surprised at how quickly those in the Risk-Monger’s social media community turned on him (and these were on the friendlier pages). This brouhaha was all because, one day, out of curiosity, I wandered into a “complementary medicine” unit in a Manila hospital for a combined session of acupuncture and cupping.

In visiting the traditional Chinese medicine section, I was taking what I had considered to be a scientific approach: I have a painful, chronic illness which is worsening so I felt I should try all possible remedial strategies, eliminate those that do not work and validate those which show positive results. I had a feeling this visit wouldn’t be helpful, but was willing to be proven wrong.

I learnt two important things this day: that my doubts about traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) were confirmed and, surprisingly, that there are many in the scientific community who are intensely narrow-minded.

My Chi is Crap!

My acupuncturist, Roberto, was a young practitioner with a very friendly demeanour. He waited patiently while I listed all of my ailments, then put his thumbs on both wrists and asked me to stick out my tongue. With that analysis he knew exactly my problem: I was pre-diabetic and my kidneys were in bad shape. I found this interesting since, from all of my blood tests in the last six months, my cholesterol and triglyceride levels were quite low and I had just had a scan of my kidneys following a series of infections and they were in good shape.

What Roberto wanted to say was that the kidneys were the centre of my life-force – my chi – and my busy lifestyle has obliterated them. Rather than a medical diagnosis, Roberto had a philosophy that was looking for validation. I was curious to learn why Roberto believed it was more the kidneys than the liver. Apparently it is because the kidneys, shaped like seeds, represent the source of life. The acupuncture was going to focus on how to restore the chi around my kidneys. In the back of my mind, I was more concerned that I should have peed before the session.

Roberto was alarmed to learn that, before my health issues, I had been an ultra-trail runner. He told me to stop exercises that drained me of energy and try traditional Eastern practices that build up energy. I was informed that runners, swimmers and cyclists all have notoriously poor levels of chi. His view is that the human body only has so much adrenaline which is kept in reserve for time of emergency (fight or flight) and that my years of over-exertion have left me almost devoid of life-force. I was bemused by his certainty on this. As many of my students can attest, every lecture I give is usually pure adrenaline, and the more I do that, or run up mountains, the more adrenaline I am able to produce. I’m pretty sure the five months with limited physical activity, paralysis and pain is what depleted me, not the running.

But maybe I’d feel better after I got “cupped”. Cupping is a traditional form of therapy going back thousands of years. Wet cupping (where the skin is cut and the bad blood is sucked out allowing chi to prosper) is a Chinese form of blood-letting. As a newbie, I was dry cupped with eight glass cups heated up to create a vacuum that pulled the skin taut (some sports therapists use vacuum suction but everyone knows those Westerners are dangerous cranks).

I could understand the attraction of cupping for masochists and those prone to fetishes, but for me, the experience was rather unpleasant. I was left alone, all cupped up, for 15 minutes; at a certain point I experienced a severe shortness of breath. Was my skin pulled too tight making it hard to breathe? Was I having a panic attack thinking that one of those cups would launch itself and land on my head. I had to stop thinking about Michael Phelps.

When I arrived, there was no questionnaire about my health conditions (just a waiver form). Roberto got everything he needed to know just by looking at my tongue and feeling my wrists. I have severe hypertension which I suppose the cupping experience had provoked. I am aware of my health issues and am still fairly strong but what would happen if someone undiagnosed and quite frail were left in isolation in such a situation? This practice was not harmless and I wonder how many people have been rushed from this hospital’s “complementary medicine” wing to the intensive care unit.

Mrs Monger was waiting for me in the lounge and had asked Roberto what was wrong with me. “Everything” he said. And that is perhaps the most attractive thing about this alternative medicine practice. After months of doctors being baffled by a patient who, within 48 hours, went from the last weeks of training for the UTMB to being unable to walk, finally there was a person who could be reassuring, confident and solutions-based. Every question I asked had a clear, simple answer, every effect had a cause; all was connected, holistic and curable. If all I wanted was an answer, Roberto provided what I needed. If all I wanted was to get better, Roberto’s holistic life-force philosophy failed miserably. I was advised I would need at least ten sessions over two weeks (at 38 USD per visit, that was no small sum) in order to rebuild my chi. I wondered how my bruised back would manage repetitive hickeys and I pitied those who put themselves through such suffering.

On the other hand, some of Roberto’s advice was simple common sense. I need to rest more, get better sleep, try to clear my head (meditate), eat properly and find proper relaxation techniques. These elements are perhaps the true healing powers that anyone should consider, rather than exposing vulnerable people to expensive pins and cups. I asked Roberto if I should also drink a lot of water. “Not too much and only warm water.” he replied to my astonishment. “It’s hard on the kidneys.”

My Science is Crap!

My second learning experience from my visit to the “complementary medicine” wing was a bit more surprising. Feeling bemused, as I left the hospital on my way to my favourite Chowking fast-food restaurant, I took a picture of my cupping scars and posted it on my social media pages. Almost instantly the harsh criticisms came in. I was called a “quack”, condemned for promoting pseudo-science, criticised for taking unnecessary risks. I was, gulp, no better than my naturopath sister-in-law, Rachel, who has clearly weakened my rational resistance.

The reactions alarmed me. As far as I had felt, testing out alternatives to better know about the other practices, to better be able to engage with naturopaths, to have experiential evidence against woo was far better than blindly accepting other people’s views that this was pseudo-science. One online encounter challenged me: What if you had felt better after the treatment? Well, I would do what any scientific-minded person would do: consider all parameters, try to replicate it and rationally examine the evidence of any causal relationship. In any case, after five months of chronic pain, heaven forbid if I should feel better (even if it were a placebo effect)!

But this did raise a good question. If I had cancer, should I try out a naturopath clinic? Many argue Steve Jobs would be alive today if he hadn’t fallen for the alternative medicine approach. This is different than taking a few hours for cups and pins. If only one route of treatment is possible, then a rational analysis at the outset is required. Of course this is easier to consider in an objective emotional state.

Others felt I was giving these people credibility. I think my assessment here and on the Risk-Monger Facebook page put that to rest. More so, they rejected my need to test out something for myself. I could just trust what other scientists had said and not give them the attention or my money. Otherwise, I would have to test everything out, including eating “Tide pods”. I wouldn’t equate talking to someone who’s views differ from mine to eating detergent or cow pies. The first part of learning is listening, but with the toxicity of today’s social media battles, taking the time to listen to people with other views seems now to be considered dangerous.

What I saw was more disturbing. I saw a group of scientists and science communicators who were intolerant to anyone venturing away from the accepted dogma.

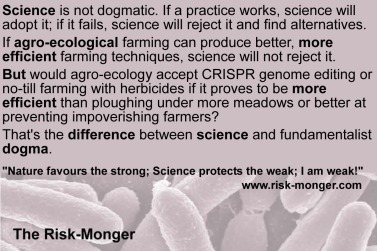

Science needs to be open, to consider all theories and methodologies and accept the best practices in a discursive manner (and not a dogmatic imposition). If it hinges on pre-ordained theories (like naturopathy or agroecology), then is it more political and religious than scientific. Science doesn’t care about your dogmatic beliefs – science searches for the most practical solution. If leeches were to stimulate blood-flow better than pharmaceutical products; if pheromones were more effective than insecticides at warding off pests; if diets could slow tumour growth … then science will embrace these practices. If science is wrong, its methodology will identify the error and (eventually) self-correct.

Science needs to be open, to consider all theories and methodologies and accept the best practices in a discursive manner (and not a dogmatic imposition). If it hinges on pre-ordained theories (like naturopathy or agroecology), then is it more political and religious than scientific. Science doesn’t care about your dogmatic beliefs – science searches for the most practical solution. If leeches were to stimulate blood-flow better than pharmaceutical products; if pheromones were more effective than insecticides at warding off pests; if diets could slow tumour growth … then science will embrace these practices. If science is wrong, its methodology will identify the error and (eventually) self-correct.

I have never considered science to be so insecure as to need to protect some dogma from challenging evidence (however flimsy or ridiculous).

Has Science Lost its Way?

Are scientists their own worst enemies? The history of science since Leibniz v Newton has been exemplified by strong personalities having disputes but their discussions had mostly been over evidence in closed circles like the Royal Institution or the Councils. In the last six decades, however, certain factors have changed the course of scientific discourse.

- Research funding has changed how and for whom research has been conducted. Where Einstein may have been able to fund his research on a Level III patent clerk’s salary, today researchers need funding from the public purse or private companies making objectives more impact or solutions-driven. Labelling a scientist as industry-funded became a tool to ostracise.

- As societies became technology-based, regulatory science grew in importance and re-framed scientific debates around policy decisions. The policy-makers’ demand for consensus trumped the scientific methodology of scepticism, challenging paradigms and attempting to falsify theories. Once a consensus was established, scientists were expected to toe the line. Labelling a scientist as a sceptic became a tool to ostracise.

- With the emergence of the Internet and online social media communities, scientific debates were no longer limited to conferences and institutes – they became public and the public demanded immediate solutions. We all became citizen scientists, with a wide variety of facts to choose from and little respect for those who may disagree. Science was being decided in a three-minute news clip, a meme or a jury. With self-taught social-media gurus challenging expertise and empowering closed communities of vulnerable people to reject technology with an ill-conceived precautionary principle, the scientist lost influence in the public discourse. Labelling someone a scientist became a tool to ostracise.

So in half a century, science has lost its independence, its methodology and its voice. And then things worsened.

Science, as an empirical process, has always been dealing with uncertainty. But as scientific debates in the digital age entered a wider public domain, the populist demand for certainty changed the nature of discourse. The precautionary principle entered as a tool to assuage a nervous population unprepared to wait for science to reach a reasonable conclusion. Certainty of consensus was demanded for policymakers to act and scientists found themselves corralled into a regulatory trap where challenging paradigms or being sceptical was considered obstructive and unwelcome.

Climate change and the contrived global urgency of an imperilled planet was the first challenge for science in the digital age. The demand for science-based policy created the regulatory need to produce a scientific consensus; something which, I have argued, then castrated the scientific process. As scientists were assaulted (funding cut, jobs lost) for even questioning the consensus, the process soon moved to one of policy-based science where those allowed to participate had to be on board with the agenda. Those challenging the dogma were ostracised. Since 1992, on climate debates, science has lost its independence, its methodology and its voice.

Scientific consensus has become a new form of religious dogma. But you cannot legitimise a consensus by silencing those free to question it. Even in cases where there is a clear consensus and science is not in question, the arrogance of authority can still bite science in the face.

The entire glyphobia insanity since 2014 was not built around science (there are very few credible scientists who would dare defend IARC’s hazard assessment). It was built around the mistrust of scientists portrayed to be acting arrogantly: trying to hide evidence, influence regulators and the media. A California court awarded Dwayne Johnson $289 million not because glyphosate caused his cancer, but because Monsanto was arrogant, tried to influence the process and did not engage in scientific discussions (protecting their dogma from challenging evidence). The fact that Monsanto’s head researcher did not return a phone call to a groundskeeper was enough to signal an arrogance that deserved righteous compensation. There was no science involved in this first glyphosate case, but rather a situation where respect for science seems to have lost its way within the anti-corporate, chemophobic societal narrative (facts didn’t matter).

Groups like Corporate Europe Observatory and US Right to Know have no scientists and could not care less about evidence. They used glyphosate as a case study in how to undermine public trust in technology, tie science to industry and help those opportunists in alternative sectors who would benefit from the public fear and uncertainty they fabricate. Those involved with these organisations are most often unpleasant individuals with grudges. But where they succeeded is in their very offensive nature. By spreading their provocations and falsehoods across a network of disaffected cranks, they created outrage in the scientific community.

Perhaps fed up with these ignorant wolves, scientists started getting into the mud and fighting back, hurling facts at these provocative activists who were not bothering to listen. The scientists appeared arrogant and disrespectful, intolerant and dogmatic. Worse, the facts these scientists used rang hollow among social media tribes who valued emotion and anecdote more than evidence, virtue signals more than data and their gurus more than recognised experts. The narrative had shifted and the scientific community was even more ostracised.

When you get stuck in the mud, chances are you have lost your way.

A while back I noticed many of my twitter trolls trying to portray me as an angry hot-head. I found this odd since I am usually quite happy and enjoy ridiculing the activist campaigns. Then I realised this was their strategy: portray all threats to the activist agenda as arrogant, angry and hostile. The game-plan was simple: provoke opponents and then show how they are not positive or trustworthy. Some of the memes they have generated on scientists who got fed up with them are lamentable and lacking in any moral integrity, but these operators know the simple rule: Perception matters.

Communicate with Confidence, not Urgency

I have often muttered that the growing number of anti-vaxxers is as much the fault of poor science communicators as it is caused by naturopath opportunists. The idea that naturopaths would willingly reject the achievements of humanity’s greatest researchers incensed and outraged the scientific community. Scientists reacted by insisting on vaccinations, sometimes forcing it upon uncertain populations (as was the case in Italy and many American states). By being forceful, arrogant and intellectually intolerant in the vaccine debate, when a vulnerable population was seeking empathy, scientists have created more fear and mistrust among parents struggling to make a difficult choice.

So whom would a parent of a new-born worried about the potential vaccine side-effects trust: a hot-head in a white coat prone to outrage or a sympathetic naturopath sharing reassuring stories?

An analogy: Imagine a world where transforming the food chain is the only way to save the planet (a stretch, but it’s amazing what a Norwegian billionaire can do). Suppose all the research data shows the only really sustainable protein source to be certain unpleasant varieties of mushrooms. As ecosystems collapse, all experts agree that the immediate transition to a fungal diet has become imperative. If I were to insist on my son the need to eat his mushrooms, he may feel some anxiety. Outraged at the thought he may not consume mushrooms for his own good and the good of the planet, I might become forceful, intolerant and apply further pressure on my son’s dietary decisions. I could even force-feed him. What is the likelihood that my son will voluntarily consume mushrooms in accordance with the scientific facts?

My son, indeed, hates mushrooms.

Being arrogant and intolerant is not a proper means to communicate science in today’s social media community-guided world. Pressuring a vulnerable person to accept facts merely pushes them to the safety of their “facts-optional” tribe. Trust today is not found in the comfort of facts but in the empathy of the community. It would be far more effective for scientists and science communicators to simply say: “This is the best evidence the brightest minds have today. If you have valuable information or would like to join the discussion, please do. We’re happy to listen to you.” Scientists instead are saying: “Don’t be stupid! Shut up and eat your mushrooms!”

But should scientists give charlatans the microphone and credibility to raise emotion-based doubts? The last time I checked, these activists and zealots are the ones being interviewed by the media and treated as the experts. So invite them to join in a debate (I do it all the time). People like Vani, Vandana and Zen will never accept your invitation. Their knowledge level may be highly questionable, but they know better than to enter into a discussion with someone who has actually studied the subject.

The scientific community’s failure to be open to even the most ridiculous theories is perhaps best exemplified with the Séralini affair. That horrid little scoundrel played the emotional GMO-pesticides narrative perfectly, provoking scientists to attack him and then play the victim card for his own personal advantage. In a recent French TV report on glyphosate (apparently a weekly serialised drama in that heavily glyphobic country), Gilles-Eric Séralini proudly displayed his paper with the word “Retracted” in bright red capital letters. Why would a professor surely seeking respect and credibility within the establishment smugly share the greatest slur a scientist could suffer? Remarkably, this petty narcissist wears his retraction like a badge of honour. The TV audience got the back-story perfectly: the scientific community has been corrupted by evil Monsanto (every story needs an identifiable source of evil), and this heroic, selfless Marianne stands bravely against the arrogant tyrant to defend the liberty of science (and the naturopath supplements company paying for his lunch). The more scientists refuse to open dialogue with this activist scientist, the more his victimisation is validated and the stronger his base believes the scientific establishment is trying to silence the truth. Putain!

Science needs to be secure in the credibility of the evidence and not arrogant to those daring to question it. The facts can speak for themselves. Let the public choose the benefits and not feel like they have to submit to relentless pressure from arrogant, alienating experts. If you try to amplify the facts, the audience may rest their ears or seek “more comfortable” facts. In many cases, the public are getting sick of listening to activist fear campaigns (but just sicker of having experts telling them what to do). Pushing harder will only create push-back. The mushrooms will not be eaten, the children will not be vaccinated and the policymakers will have a hard time selling climate mitigation measures on a free-thinking population.

*******

So the Risk-Monger may be ostracised by arrogant, alienating experts who feel a need to lecture him on the foolishness of traditional Chinese medicine. Did he lose his way or did the scientists who felt the need to keep him “in their column” forget the critical aspect that has served science so well for the last 400 years? Like any other individual, David is capable of thinking for himself. In this case, he decided that it is indeed, as expected, a pseudo-science (and then he bought some ointment for his back). Many other individuals though, may feel threatened by such provocation and seek trust and validation in tribes that protect people from such aggressive arrogance. And whose fault is that?

When you lose your way, it might be a good idea to change your ways!

Point taken in talking about things like glyphosate and GE. Yes, some scientists can be arrogant, some are poor communicators and still others are susceptible to influence of many kinds, but to include things like TCM and homeopathy in the conversation is to misunderstand what constitutes legitimate areas of scientific inquiry.

The principles that underpin TCM and homeopathy are based on magical forces that cannot be observed. Gravity may be a rather mysterious force, but you can measure it, develop theories and make predictions based on those measurements, and falsify claims. When one is dealing with qi or homeopathy’s “vital force,” you can’t do any of those things.

Those who promote and defend the practice of homeopathy, naturopathy, TCM, chiropractic subluxation, etc., are desperate for reasonable people to talk of them as if they are legitimate medical interventions, and for that to happen, one has to redefine what science is and lower standards for evidence to the point of its virtual absence, as in: “I don’t care what you say, I know how I feel.” That is exactly what we don’t need, we need to make science better, not replace it with anecdotes and testimonials.

LikeLike

I think I chose to use TCM because it is such an extreme box of nonsense … but the discussion then drifted to glyphosate and Séralini. The same principle applies. I feel the more we shut dissenters out and rally around a consensus, the more we advance the popularity of their pseudoscience by creating victims and heroes.

LikeLike

Shutting dissenters out is not the same thing as lending them credibility by suggesting that magical thinking is susceptible to evidence. Actions such as yours actually can do harm by advancing the idea that TCM is just benign hocus pocus, that it couldn’t hurt to give it a try if one hasn’t found relief in science-based medicine. People have been harmed; TCM and other “alternative” interventions are not just benign magic tricks. Sure, don’t be a jerk and make martyrs of TCM practitioners, but don’t give such ideas any more credit than they deserve, and they absolutely do not deserve putting one’s health at risk regardless of how small that risk happens to be. That’s not dogma, it’s reason.

LikeLike

Important points, thanks George. I am not too worried that my readers risk turning to TCM – I have a more refined audience.

What I tried to do in the front end of the blog is to practice what I preach – to present TCM in a critical way which was not arrogant – not using words like “hocus pocus” which would stiffen resistance and sympathy among potential naturopaths. But the criticisms were there – I noted how TCM is dangerous, no real analysis, no background health check, no validity of diagnosis but I tried to express it in a way that was meant to be tolerant (even offering how some of Roberto’s advice is common sense). I’m curious how a TCM practitioner would respond to my approach. If we can discuss pseudo-science in a less “science is everything” dogma, perhaps there would be fewer anti-vaxxers and anti-GMO campaigners reaching large audiences of vulnerable people.

I tried to write this blog in a demonstrative way, but I am afraid it failed miserably. On the Risk-Monger FB page, there are about 70 comments over the last two days, mostly angry, by people who normally agree with me … I fear they did not get my message … at all. I suppose people have to be aggressive today with their views … and so vulnerable people are turning away from scientific practices.

Maybe I tried too hard on this one.

LikeLike

I think the problem your usual supporters have with what you have done is that no matter the outcome (getting better or not) that wouldn’t serve as any kind of scientific proof. But by saying that “I tried, I dind’t get better ergo it doesn’t work” is exactly the same flawed arguments the defenders of TCM use.

You have undermined all the evidence and confidence there should exist about the useleness of TCM by showing you are willing to try it.

It’s not about challenging the scientific consensus because, like I said in the beginning of my comment, what you did has no scientific validity. After all testimonials don’t validate treatments

LikeLike

“I don’t care what you say, I know how I feel.” That is exactly what we don’t need, we need to make science better

I think this exactly reflects the issue. When scientists seem ignore people’s feelings, it is no surprise that people reject science.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think a great many, including me, “get your message,” they just don’t agree with it and are concerned about the corrosive effects (sometimes, quite literally) that TCM can have on peoples lives. Some folks have the same feelings towards quackery and those who practice it as you do for predatorts. In my mind, the only difference between the two is that TCM has been around longer. I have plenty of sympathy for those who desperately seek “alternative” interventions when modern medicine cannot provide solutions, and nothing I said was directed towards them. I save my vitriol for the charlatans who exploit them.

LikeLike

Favorite Risk Monger blog EVER in all the years I’ve been following you, David. It’s like “Better Angels” but for science communication, and I hope a lot of your other fans take it to heart and give it some thoughtful consideration. Thank you !

LikeLiked by 1 person