- I’m frequently criticised by smug trolls who conclude I am not a real academic as I do not have many articles in academic journals.

- A lot of my research goes unreferenced or writers in journal articles source my work and concepts in the name of the journalists who amplified it (since I am “just a blogger”).

- My candidacy for several academic positions was passed over due to my thin academic bibliography.

So why don’t I just publish my articles in some academic journals or news organisations?

Academic journals have become more a tool in lobbying and activist campaigns than any academic endeavour or knowledge exchange. Journal editors often seek controversial headlines and click-bait rather than sound methodology. Replicability of findings no longer seems to be a valid question or an issue for retraction. University communications departments try to generate buzz and media attention for the smallest of citations. Activist NGOs and tort law firms see a “peer-reviewed article” in an academic journal as pure campaign gold (for the price of silver). But where is the scientific value and integrity in this process?

An “Unfixably” Broken Process?

20 years ago, when I was finishing up my doctoral dissertation, it was expected that I would begin to publish segments in journals (this was before the proliferation of online predatory journals). I looked at the structure of the publishing world and decided it wasn’t worth it even back then. Today, some PhD programmes don’t pay much attention to a dissertation but expect you to have at least five academic journal publications (citing the candidate’s affiliation with the university naturally ). These graduates, as professors, usually demand their students only cite from peer-reviewed sources.

The peer review system at the beginning of the millennium was already showing signs of breaking down. As publishing revenues sank in the digital evolution, journals continued to charge more to universities for subscriptions. Some universities staged a boycott of the main journals (particularly Elsevier) leading to a movement toward open access publishing (with two main approaches commonly called green and gold open access).

With open access, the financial burden shifted towards to author being expected to pay the publication costs. Peer review management fees quickly escalated from below 500 USD to above 2500 USD on average. Many “predatory journals” claim they have a peer review process but are merely “pay-to-play” publishers putting any article online once payment was received. While academics started to focus on impact factors and h-index rankings, as you could imagine, overall quality did not improve as opportunists, activists and B-grade researchers started flooding online journals.

The Pee-Review Process

At the same time, with more academics bowing to the publish or perish mantra, many new journals started to spring up using the online open access models. When Springer started getting into the game, they polluted the quality even further. In the digital world, online vs print did not matter and nothing would stop a predatory journal from releasing thousands of pages in a quarterly.

Some journals simply published gibberish once the cheque had cleared. It is argued that half of the articles published are not read by anyone. But the cheapening of peer review is not only limited to online organisations with bank accounts in West Africa or the Gulf region. Following the Sokal hoax in the 1990s, three scholars recently got a number of ridiculous articles through peer review in high-profile journals (this prank was known as Sokal Squared).

Why then do people legitimately play this game? Often academics pay these sharks to pad their bibliography, improve their h-index or raise their ranking in Google Scholar with more (self-generated) citations. Their universities expect a certain number of publications and provide a budget for peer-review publishing fees … so it becomes a meaningless numbers game. They pretend to publish and we pretend to read them.

I prefer to call this the pee-review process since people who pay to print their rubbish (knowing full well the credible journals would never allow it to see the light of day) are merely pissing on academic credibility. It is a cynical game played by people who sadly lost inspiration and simply show up in lecture halls to receive their salaries. And this stench emanates upon their students who have accepted this erosion of integrity as the norm.

Some of my friends in the academe have created online journals – it’s not hard. They use their academic mailbox and hire a grad student to manage the emails and website (it seems nobody ever asks what their impact factor is). No one can deny that being an editor or founder of an academic journal looks great on a CV and pushes you up to keynote status at conferences. And maybe the grad student can get an eager and motivated undergrad to organise the peer review process to pad that paltry academic stipend.

Peer review or friend review?

I often get requests from journals to referee a proposed paper. Invariably I am referred to by the author of the paper as a potential peer reviewer (ie, someone who will likely agree with the views in the paper). I decline these requests on ethical grounds. A peer review should be intended to challenge the paper’s contents (in keeping with the scientific method), not to find a friendly voice to rubber stamp and promote further bias. And if a journal is collecting 2500 USD to conduct a peer review, then isn’t that the editor’s only serious job?

This has led to the Ramazzinification of the publishing process. Collegium Ramazzini is a private club with a limited membership of prestigious occupational and environmental scientists – sort of a Rotary Club for activist scientists. Based in Northern Italy, its membership consists mainly of American regulatory scientists who make the pilgrimage each autumn for a number of days of fine wine, secret handshakes and special projects. They peer review each others papers and cooperate in advancing each others careers (eg, by nominating each other onto IARC panels leading them into the lucrative world of litigation consulting).

The membership process to join this esteemed institute is more value and politically-driven than scientific. Ramazzini has even funded its own journal for its peers to more easily pee-review papers among themselves. It is The Journal of Scientific Practice and Integrity and given the questionable practices and challenged integrity levels of many of their members, their byline should be: “Pot, Kettle, Black“. You really can’t make this stuff up.

Portier’s Science or Tort Consulting?

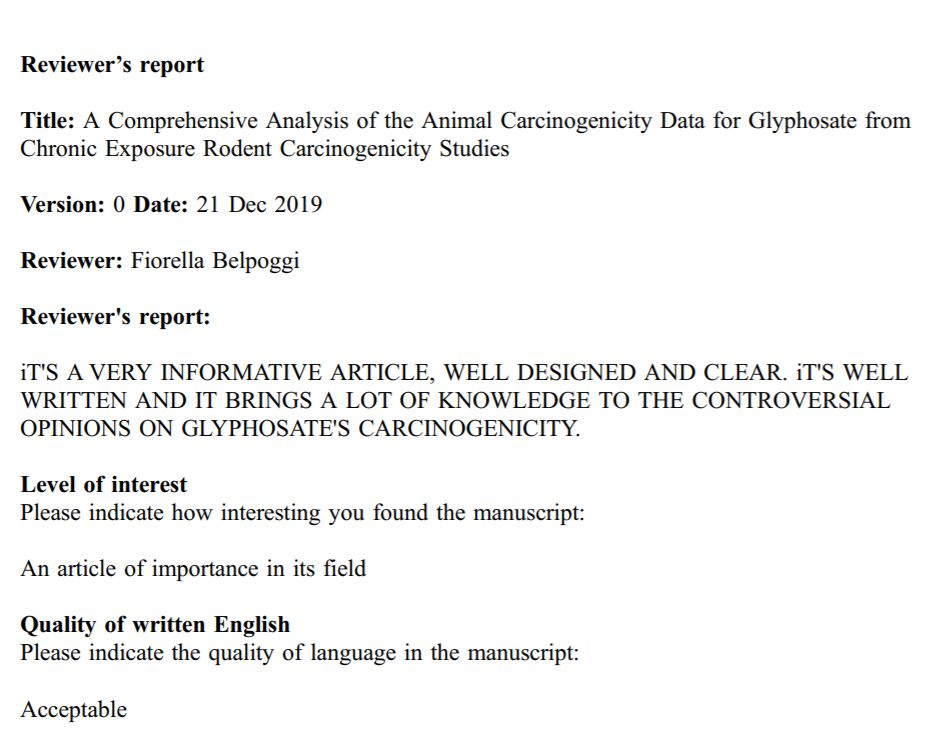

Recently Ramazzini member Chris Portier reprocessed some work he did for US tort law firms suing Bayer on glyphosate into a paper published in Environmental Health (in order to help tort lawyers make the case in front of juries). Curiously, the three peer reviewers were all very critical of glyphosate and friends of Chris (including the head of Collegium Ramazzini, Fiorella Belpoggi) and quelle surprise they were all glowing about Chris’s work (see image illustrating the depth of Belpoggi’s critical peer review of his submitted paper).

Once Portier’s paper was published, the Altmetrics page showed how his good friends in the activist community, from US Right to Know, Children’s Health Defense, Mercola and LeMonde’s relentless two Stéphanes amplified this work as fact.

Why did Portier recommend these anti-glyphosate activist scientists to rubber stamp his article? Doesn’t the objectivity of the peer reviewers matter to an academic? Did he not think his research could withstand the scrutiny of the scientific community (or did he not care)? He declared his research was paid by US tort lawyers (benefiting from “scientific evidence” they could then use in their glyphosate lawsuits). The only thing Portier achieved in this cynical process of paying to have his Predatort-funded anti-pesticide, anti-Monsanto rhetoric published is a further demonstration of how endemically ethically challenged he is. Activist science at its finest, abusing the peer review process with recidivistic research practices.

Low Readership, High Amplification

If almost half of the articles published in online journals are not read, and a good number of the others read less than a hundred times, why would anyone go through the process, cost and hassle? Like Portier’s US tort law firm paymasters, many of these journal publications are campaign strategy seedlings.

Bee-Gate exposed how a group of activist scientists set up an “IUCN Taskforce on Systemic Pesticides” to produce a large body of academic papers (where the conclusions were predetermined and would lead to the banning of a group of neonicotinoids). Their strategy was to have their yet-to-be-determined scientific “breakthroughs” published in some “high-impact journal” (maybe Science or Nature!!!). This group of activist scientists shared a rather cavalier attitude towards academic journals, discussing how to get a science PR professional to handle the publishing details. Members of this taskforce would then recommend each other to peer review their papers. The next step, according to the architects of this scam, would then be to have their “science” amplified via a few major NGOs like WWF. In the end they could only get their articles accepted in a low impact factor pay-to-play journal and most NGOs (including, eventually, the IUCN) took a good step back from this ragtag group.

NGOs are generally not perceived as being scientifically strong, so the first step to close this credibility gap is to get some campaign material published by some academic with an axe to grind in a sciency sounding journal. Once a researcher is paid to publish their position paper, the NGO can then amplify the article in their campaigns. The speed at which some B or C-grade researchers can be feted as activist media darlings can sometimes seem almost “Goulsonic”.

Professor Ruskin

This technique is becoming textbook (and some activists are being shamelessly open about it). Cue one rather low self-esteemed activist called Gary Ruskin. His modest organisation, US Right to Know, spends tens of thousands of dollars every year to fund academics to publish Gary’s campaign material in “peer-review” journals and then they pump out articles and press releases claiming the “science”. In 2018, US Right to Know paid European academics 134,000 USD to publish their campaign material in journals. They did not disclose to whom and how much, but merely provided a list of their “peer-reviewed articles” and their activist media amplifications on a page called Academic Work. They even paid to get the anti-vaxx, anti-5G freelancer Paul Thacker to publish a viewpoint in the BMJ on the evils of Coke (to which a correction was later issued acknowledging US Right to Know as the source of the research).

US Right to Know’s IRS filings book the funding for these publications as non-disclosed contributions to writers in Europe. Why would an American activist lobby group pay so many academics in Europe? Unlike the US, most European academics are not subject to FOIA requests in the same way as in the US academe, so no one can see how these useful idiots are paid to jump through hoops for Gary Ruskin’s anti-capitalist agenda. Gary puts his name on every article published, and although he actually wrote the cheque, in the Acknowledgements section, funding was often credited to the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, US Right to Know’s largest donor at the time. That way it doesn’t look like Gary had to buy his way into the party.

US Right to Know demands transparency from others, but not themselves. They attack industry for ghostwriting and yet they pay academics undisclosed amounts to publish their campaign materials. They attack lobbyists who pose as journalists and yet Carey Gillam still refers to herself as a journalist (while US Right to Know pays her rent). Now they have made a joke out of the peer review process.

The biggest joke in all of this is that if one took the time to read the articles, most are of an extremely poor quality. The point is not the journal article (these are rarely read) but how their claims are then amplified by US Right to Know in the broader media. If we paid to have it published in a peer-reviewed journal, then it must be a fact! How long before the media and policymakers wake up and realise most of these publications are meaningless (“in mice”).

Groups like US Right to Know or the IUCN Taskforce on Systemic Pesticides make a mockery of the peer review process for their own campaign agenda. This broken process is allowing white-trash intellectuals the pretence of academic credibility. Let’s not forget the day the French feral journalist Stéphane Foucart proudly referred to himself on twitter as a peer-reviewed author. That little Young Turk has issues that would make Gary Ruskin look like a UCSF professor.

Politicised Editors

One of the saddest points in the last decade, during the decline of journal influence, is how spineless journal editors have become. Often they seek controversial topics (even if scientifically barren) for the mere pleasure of click-bait. Other times, when pressured by activists or arrogant egos, they buckle and retract papers that challenge the consensus (what science is supposed to do).

It is rare today for journal editors to stand up for science and integrity (why so many raw egos think they can push editors around). In Part 4 of my 2019 IARC Dirty 30 series, I showed how this WHO agency was trying to use its influence to pressure the European Journal of Cancer Prevention to remove or strongly edit a paper they had published online by Robert Tarone that was critical of IARC’s glyphosate debacle. They managed to delay the print version of Dr Tarone’s paper by over a year but kudos to the editor, who withstood IARC’s bully tactics and baseless threats of a COPE investigation unless the WHO agency got their way. Most editors would buckle under the pressure of such institutionalised bullying. Even more remarkable was that Tarone’s article went against the sensationalised, chemophobic click-bait spread by the Ramazzini cabal.

And it is getting worse. Now publishing your views anywhere is a bit of a whack-a-mole retraction game where skittish editors from Medium to Forbes to Elsevier take articles down the minute an activist group gets together and declares: We’re not happy with this! The well-known environmental science communicator and nuclear energy advocate, Michael Shellenberger, for example, recently had an article taken off of Forbes within hours of publication because he dared to suggest the climate death-cults’ forecast of the end of humanity within ten years was not factual. In today’s cancel culture, you are not allowed to question the consensus.

Four years ago I saw how the editor of my blogpage on EurActiv was continually running from complaints and changing or removing my texts. Knowing the history of communications in the 1930s quite well, after a spat about IARC and glyphosate, I decided to go completely independent and while I did give up much of my passive following, it has allowed me the freedom to publish whatever I uncover. While my trolls had to then go after me personally, I am fairly certain that if I had continued to rely on an editor wary of complaints, articles like the Portier Papers, EFSA’s cover-up of the draft Bee Guidance Document COI, my Monsanto Tribunal stunt or IARC’s Dirty 30 would never have been allowed to see the light of day.

Bottom Line: Why Bother?

Simple question: Why should I bother to publish in peer-reviewed journals?

I could pay 2500 USD to go through a process where I inconvenience my friends to give their time freely to peer review my article in order to get it into an online journal publication where, maybe, it is opened 150 times and cited by 5, four to six months after I had written the article (eg, six months ago, we were in a pre-COVID-19 world) and then deal with people whose political bias clouds their capacity for rational thought continually writing my editor demanding the retraction of said paper because prior to 2006, I had worked for industry.

Or…

I can write the same article, put it up immediately on www.risk-monger.com, exactly how I want it, watch it read and shared 10,000 times on the first weekend by a largely academic crowd who then engage with me in the comments section, via email or my social media pages, amplify it on their own websites, translate it and republish it in their national organisations, share it on their course reading lists or office news compilation services. I do that 30-40 times a year to encourage more open thinking.

Hmm, I’m not sure where the future of peer review publishing is going, but I’m sure where I’m going (and I suspect a lot of others are following me).

My personal belief is that the scientific “peer-reviewed” enterprise is broken. In too many fields, peer review has devolved into looking for the “right” references and away from vigorous and rigorous criticism. Too many experimental results can’t be reproduced. Unverified and unvalidated modeling edifices are built, and then defended as if they were bastions of truth.

In my nuclear waste career, I was required to validate work done several years before. My bible in doing this was the NRC’s guidance on qualification of data (NUREG-1298). It recognizes four methods:

• Confirmatory testing. Performing testing that gets the same results.

• Corroborating data. Providing existing data or data sets that support the correctness of the results in question.

• Evidence that data were collected in accordance with a relevant quality assurance program (in this case, consistent with 10 CFR 60).

• Peer review.

By far, confirmatory testing was the most effective. Of course, we can’t do that for every published paper. But what we might do is to require that our journals begin to demand that researchers provide information on the quality of their data – both inputs and results, things like repeatability, uncertainty and so on. We need to find some way to restore the credibility of the research enterprise.

Peer review is not what it used to be (if it ever was!). I see it all too often as the last refuge of scoundrels – friends approving friends’ papers with limited review but attacking new results (esp. from unknown researchers) which cast doubt on received wisdom.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this – I did not get into what should replace peer review (I thought about it at the end when I spoke of my own publication process but this was already too long). I suspect there will be a type of professional crowd-reviewing – so papers are put online and professionals in the field will all comment on them, share their replication/falsification experiences and then they will be rated (blockchain publications) but that will take a further evolution in the trust tools and a diminishing of the tribal political divisions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good points. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I was doing my earth and biological sciences training in the 70s and 80s it was already clear that many of the journals were publishing rubbish. This was less so (then at least) in the traditional ‘hard’ sciences such as geology and microbiology. It was already hugely obvious in the fields, such as ecology, that attracted ‘believers’.

LikeLiked by 1 person