I recently received a request to participate in an international study on sustainability policies. They told me my input was desired because of my: “important contributions to the peer-reviewed literature in sustainability”. OK, they got my attention and as the survey was “led by researchers from the University of Bern (Switzerland) and Lund University (Sweden)”, I decided to give them the ten minutes of time they had promised it would take.

That’s ten minutes of my life I’m never getting back.

The researchers from these two leading European universities stated:

Our study explores the potential of different sustainability policies to reduce ecological footprints, secure well-being, and increase social equity. By sharing your perspective, you will help us generate representative data on expert views that can inform future research and policy decisions.

When I read the first series of tick boxes, I thought “Oh dear! Is this scientific research or political dogma?” They built bias into a questionnaire to try to prove their ideological agenda. Not only did the scenarios assume sustainability policies were equivalent to the degrowth strategy and a rejection of innovative technologies, it put forward a philosophy of political governance by civil society, citizens’ panels and citizen audits of regulations. There was no space in their “research survey” for alternative ways of thinking (like advancing sustainability via innovative technologies, economic growth and product stewardship).

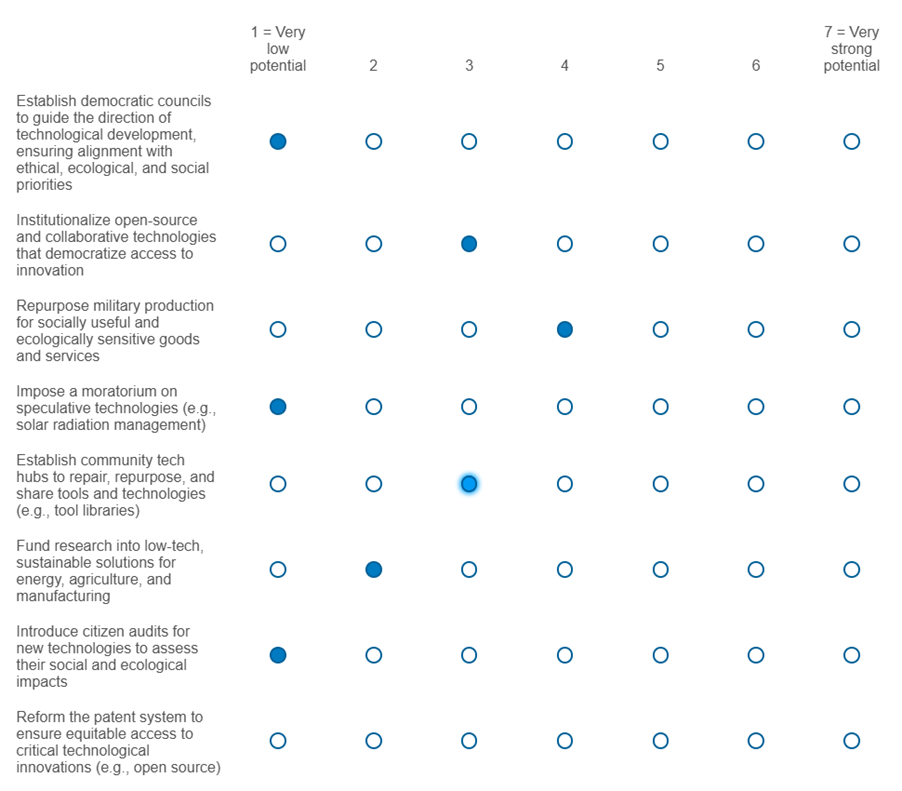

These eight degrowth policy options kept coming back on all of the questions (although reordered for deception), nuanced in a way to persuade the survey participant that it was only possible to have sustainablity by radical social, political and economic transformation. I was only allowed once to suggest an alternative idea to improve sustainability, but that would have little influence on the research results.

Here are the survey options for each question.

Eight Ways to Express Bias

The Lund/Bern researchers decided that any sustainable solutions could only be based on an anti-technology, degrowth, public ownership and citizen panel mindset. Capitalism was declared dead by their doctoral supervisors more than a decade ago, and anyone who thought that the present economic-industrial system could provide solutions was simply flogging a dead horse. Fortunately these were academics, with no influence or contact with the real world, but their students or those amplifying their conclusions in the media may assume they have a certain experience, expertise and, dare I say, wisdom.

Anyone who looked at their eight sustainability policy options though could safely conclude that these researchers have neither experience nor expertise (and wisdom had definitely escaped them). For example:

- Establish democratic councils to determine technology policy. These types of citizen panels risk promoting the interests of the affluent over the needs of the majority. People with full bellies or those who can afford solar panels on their rooves should not be exercising their ideological dogma on populations that are hungry or energy impoverished. At best, these consultative bodies could suggest long-term ideals, but should never be allowed to dictate policy. The researchers also suggest these “democratic councils” consider the ethical priorities of such technologies. This already exists and functions very well as ethics panels found acting autonomously in universities, hospitals and companies (but rarely active in the social science faculties in Lund and Bern, I suppose).

- Democratize access to innovation. Like citizen panels, the ambition here is to restrict industry involvement in the innovation process (assuming that industries will always pollute and put profit before planet). But the innovation process, with the heavy investments they entail, depends on a financial reward to compensate the innovators. If a company with a product in a highly competitive market can innovate or iterate so as to make it more energy efficient or needing fewer production inputs or materials, then they should benefit from their first mover status. … Unless, perhaps, if you are a researcher from Sweden or Switzerland.

- Reform the patent system to ensure equitable access. As in point 2, taking away patent protection, intellectual property rights or copyrights goes against the key drivers of innovation and creativity. It destroys any market incentive to advance sustainable innovations. Patents allow for greater investment in research and development which inevitably leads to better, more efficient technologies. Open source does not deliver more innovation because it lacks market incentives and long-term management. If the patent system were to be reformed, intellectual property rights should be extended and lengthened so that certain research-intensive companies (eg, in the pharmaceutical industry) have more time to recoup their investment, lowering prices and increasing access.

- Repurpose military production. As the first casualty of war is the environment, who would argue with the idea of shifting production away from weapons systems into more green technologies? Except that reality is continually confronting this flower-child dream. With at least five hot wars presently ongoing around the globe, peace and security issues are pressing heavily on government asset allocation. The addition of this policy option to the survey not only affirms the naivety of the researchers’ bias but also reveals how little they understand about risk management. Risk management involves the risk-risk paradigm (ie, will my decision lead to other, greater risks?). If a government decides not to produce military weapons at a time of security threats, because it is not environmentally friendly, will they be putting their citizens at a greater risk?

- Impose a moratorium on speculative technologies. The bias here is that technology is dangerous and should not be an answer to sustainability. EVs, solar panels and gene editing were all, at one time, speculative technologies. Moratoriums are precautionary by nature and only allow research to move to other locations where the technologies can advance perhaps according to other priorities. The researchers mention solar radiation management as an example of a threatening technology that should consider limitations. I suppose they mean solar geoengineering, which could entail some risks but is certainly managed and monitored (especially given the size and costs of the theoretical projects). The researchers presume that these scientists are all running amok trying to destroy the world with untested, expensive technologies.

- Establish community tech hubs and tool libraries. My local commune has a monthly repair café and it is a great way to save money and reduce consumption by getting retired tech wizards to fix my broken appliances. Would this practice ever be part of a significant policy for sustainable technological solutions? Not really.

- Fund research into low-tech sustainability solutions for energy, agriculture and manufacturing. I am not sure what the researchers would define as a “low-tech solution” and why it matters. Every problem invites research into a solution and the cheaper (lower) the solution, the better. Growing up on a farm, we were always trying the easy solutions to challenges first so this point of prioritising funding shows how little the researchers understand about innovation within a problem-solving context. This policy option also indicates the researchers’ aversion to high-tech at any cost.

- Introduce Citizen Audits on new technologies. Once again, this prioritising of the non-expert, participatory approach would have, as its objective, the imposition of an activist stakeholder control on the innovation process. Why call it a citizen audit rather than a stakeholder consultation? The implication here is that an audit involves a decision to interrupt research projects while going outside of a regulatory or risk management process. The implication here is that the researchers involved in this study don’t trust industry, innovators, government regulators or technology in general in the process of developing sustainable solutions, and have built this distrust into their research. The expectation (objective) of the Bern and Lund university teams is that non-expert citizens will invariably fear new technologies and consistently vote against them.

The researchers’ agenda is simple: First we make the public afraid, and then we make them govern us.

Part of the personal details that the survey required from me was to provide the year I received my PhD. Isn’t it curious that in a survey trying to lead their conclusions toward citizen governance, non-expert audits and public, participatory panels, that they would only rely on the data provided by those deemed as “experts”? I suppose the researchers could not trust that “peasants” would understand the nature of their questions (but they seem OK trusting such non-specialists with making decisions about emerging technologies that might promote sustainable innovations). Or maybe if they had gone up to random people in the street and asked them if they wanted to be governed by people with no expertise or experience, their responses might conflict with the researchers’ political agenda.

Shepherds need their sheep to act as expected, but not to act on their own research.

What Happens Next?

Depending how the researchers will manage their data, my responses will likely be filtered out within the bottom 10%. As the participant selection pool was known (it was not a random call) there will be a significant number of researchers whose answers will fall within the intended bias of the study. The paper the researchers will then produce will argue that experts feel that citizen engagement in the decision-making process is the best way to ensure sustainable policies and stress the necessity to use these panels to protect humans and the environment from any emerging technologies, patents, and large industry-led research. This conclusion will be drawn without even asking the “expert participants” if technological innovations might be able to promote sustainability.

There is a certain trick behind their survey bias. I found myself giving a score of 3 on 7 for the existence of open source research or community-based repair cafés. They are not bad things in themselves, and as a “nice to have” (however useless), they would not be marked down. So I found myself providing a moderate score to something that was not really a significant policy option to promote sustainability. Reducing regulations and incentivising sustainable tech investment are much better examples of sustainable policy options but they were not within the parameters of the survey so would not be considered in the final publication.

The paper itself could be published in a wide selection of “peer review” journals (that favour studies promoting climate and sustainability). The authors will likely submit it to a pay-to-play journal (their universities will cover the €3000-4000 publication cost), and the journal will probably ask them to propose the names of potential peer reviewers (ie, sympathetic colleagues rather than critical Risk-Mongers). Quality or integrity is rarely a factor in academic publishing today (so the 15 or so names likely authoring this article can be assured of a yet another title on their vanity list of publications).

Upon publication, the interest groups that funded the research (probably via a degrowth, tech billionaire foundation) and the NGO / post-capitalist activist community will amplify the results of this “ground-breaking” research.

When bias enters the research process, it almost always indicates some external interests.

As the journal editors and a large proportion of the social science research community generally share the same anti-industry, precautionary mindset, there will likely be no serious critical reaction to the article’s findings or lack of scientific objectivity or rigour. It will be cited in other useless political activist articles that no one ever reads, pumping up the journal’s impact factor.

And that, my friends, is how the academe is able to develop, promote and publish bullshit.

__________

Enjoyed this read (free with no ads)? Support The Risk-Monger via Patreon.

Become a Gold-Monger patron for 5 € / $ per month and get David’s newsletter.

Academe – and its spawn, peer review: the last refuge of scoundrels!

LikeLike