See the French translation

You might be reading this on your laptop in a comfortably warm Uber you arranged on your smartphone via a website storing your data in the cloud. The car is a hybrid built with advanced polymers, chemicals and repurposed plastics. The coffee in your cup (recycled from used chewing gum) was freshly ground, with an attractive hazelnut aroma, paid for via an electronic payment system on your watch while you bite into a crisp apple (in March) that was perhaps three days off the branch. All of this is happening every day in cities like Manila or Shenzhen – something that could not have been dreamt of a generation ago.

You are benefitting from a large number of corporations that have made this moment possible. But before turning to read this blog, the last three messages you had received probably had focused an indignation towards industry, business and the corporations that have developed the products, tools and services allowing us to live longer, more comfortable and prosperous lives. Still we are told our cancers, illnesses, shattered economy, polluted seas and poisoned earth result from some divined corporate neglect and malfeasance.

How is it that, like spoilt little brats, the more we have received from industry, the more the public is filled with rage towards them?

Shared Myths of Corporations

Seeing media portrayals of corporate greed in the New York Times, watching anti-industry documentaries on Russia Today or Al Jazeera, clicking through activist campaign websites or reading my own cabal of troll accusations, I have come to the conclusion there are two types of people in this world: those who have worked for industrial corporations and those who haven’t but, looking at companies from the outside, seem to have a strong critical position against them.

Having worked until 2004 for the largest Belgian industrial group, I put myself in the former group.

Surely, Mr Monger, you are generalising and a bit dramatic at that! There must be a good percentage of the population between these two poles.

How about the academe?

Well, in my experience, if you come from industry, you are often distrusted by your colleagues or left to fester as an adjunct (usually both).

How about government?

At least in Europe, it is becoming quite difficult to get (and keep) a position in public service if you are coming from industry.

There is a large audience of passive onlookers who don’t know what to think, but with every egregious attack on industry, amplified across social media tribes, their perception is more influenced by the ignorant classes.

But maybe we should ask some obvious questions.

-

Have you ever wondered why there do not seem to be many former corporate executives now working for NGOs and telling the world the truth about how corrupt and deceptive industry is?

-

Have you ever wondered why the characters and spokespeople in anti-industry documentaries have never worked for industry?

-

Where are all of the expert internal witnesses to the corporate ecocide and crimes against humanity we seem to hear about every day from the likes of Vandana Shiva?

We do have many high-profile campaigners who have left their NGOs and spoken out about the problems in the activist movement. You would almost expect the NGOs to take those who have left industry to join the ranks of the “morally just crusaders” and parade these trophies around all media outlets. Maybe these NGOs are just too modest and respectful.

Isn’t it always the case that the people with no real idea on what they are talking about seem to be the ones doing a whole heap of the talking. And anti-industry activist groups like Friends of the Earth, Transnational Institute, US Right to Know, Corporate Europe Observatory, SumOfUs and Avaaz do seem pretty sure of themselves when they bash industry. Pity none of these groups seem to employ former corporate executives with inside experience to legitimise their assumptions. So in their vacuum of misunderstanding, allow me to dispel a few of the myths they ignorantly spread.

- Most people in companies do not receive huge salaries. The media love to highlight the lucky few receiving bonuses and executive pay packets, but most corporates are working long hours for an average salary, being regularly reminded that their company may have to restructure to cut costs. My salary as a middle manager with a PhD working long hours in a corporate headquarters was less than I make as a lowly “docent” with three days of lectures a week.

- Corporations have (and exercise) very strict moral codes of conduct. When you are under the microscope by vigilante groups who want to shine a critical light on you, then you don’t mess around with morally questionable behaviour. Most multinationals do not operate in areas where corruption is rife. If their code of conduct says you must not pay bribes, then there is no point playing in that market. Public companies are also accountable to shareholders who apply a bit more scrutiny on finance and governance than most donors to NGOs.

- People working in companies care deeply about making the world a better place. In the chemical-pharma company I worked for, I was proud that our specialty polymers were essential for producing lighter, more efficient technologies (from cars to medical implants); that our chemicals were developing better types of home insulation and more affordable solar panels; that our drugs and disinfectants were saving lives and improving human well-being… People who did not believe that would simply leave the company. It is extremely disheartening for people working in such companies to see industry portrayed in the media as polluting playgrounds, knowingly causing cancer and telling lies (often spread by jackasses with no experience in industry).

Companies have been acutely aware of this negative perception cast upon them and have taken many bold initiatives to address this (they need to keep attracting the best recruits out of school). We have seen many standards to make companies better including Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and Corporate Citizenship, but for me the most impressive concept to improve corporate performance has to be Product Stewardship.

Stewards to the Environment and Public Health

Product stewardship developed as a corporate concept in the 1990s (while instances can be found from the 1970s) as a commitment to reduce or minimise environmental impact by continuously improving systems, products and processes throughout their entire lifecycle. This stewardship approach developed out of recognition that the industry ways of the 1970s and excesses of the early 80s were unacceptable. Product stewardship initiated a “contract” allowing industry to have the right to produce, or rather, should industry not seek to continuously improve, they would have that right taken away.

We can see a history of product development based on continuous improvement.

- The first generation of mobile phones emitted enough radiation to pop popcorn. Continuous research and innovation delivered a series of safer technologies.

- The early pesticides in the 1960s were quite harsh on the environment and the users, but decades of refinement have lowered the risks and, with the next generation of improvements, precision agriculture could cut pesticide volumes by up to 80%.

- Pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers are transforming what used to be life-threatening surgical interventions into non-invasive, outpatient treatments.

Despite decades of product stewardship, crop protection companies and farmers are still being judged by groups like PAN and EDF according to 1960s technologies. Pharmaceutical companies are considered by activists like Mercola or Ty Bollinger as part of the “cancer industry”. Rather than acknowledging the achievements of continuous improvement, the attacks on industry are getting more severe as these NGOs have monied up and social media makes public fear campaigns more effective.

After several significant industrial disasters in the 1970 and 80s (Bhopal, Seveso and Love Canal), the chemical industry introduced a voluntary commitment, the first of its kind in any industry, called Responsible Care®. Established in 1985, this became the foundation for concepts like sustainability, product stewardship and transparency. Today these best practices extend across 60 countries covering 90% of the global chemical production chain. These concepts were not the brainchild of any NGOs back in the 1980s. The achievements of product stewardship were not imposed by regulators. These were commitments coming directly from the chemical corporations. Activists ignore these achievements that have delivered more than three decades of safe chemical production and often harp back on Bhopal and other events from 40 to 50 years ago as if nothing has changed.

With product stewardship came the focus on the lifecycle of a product. The first lifecycle assessments looked at cradle to gate (only the manufacturing process), then cradle to grave (to integrate how post-use recycling was managed) and finally from cradle to cradle (a commitment to zero-waste). Other sectors adopted similar processes of integrated risk management (farm to fork, boat to throat…). These developments, once again, came from industry initiatives.

“That’s just not good enough!”

The last generation has witnessed no major man-made industrial accidents. We are extremely fortunate to have not had a major crop failure anywhere in the world in the last decade. We have been able to see developing countries emerge into modern, capitalist economies through free-trade and open markets. Every time I go to South-East Asia, I am floored by the speed of development and the confidence of their outlook. Western consumers are benefitting from the deflationary pressures and access to goods from systems put in place not by governments, but by multinational corporations.

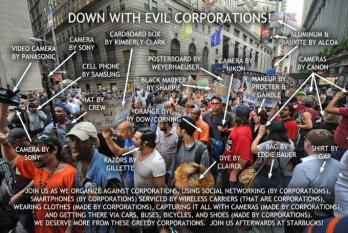

Indeed we have grown fat and lazy, both physically and mentally. We wag our finger aimlessly saying “That’s just not good enough”, lurch out of our comfortable sofas just long enough to march against the system and then go back to enjoying the benefits while succumbing to the slick, green solutions put forward by the idle, privileged and ignorant.

Indeed we have grown fat and lazy, both physically and mentally. We wag our finger aimlessly saying “That’s just not good enough”, lurch out of our comfortable sofas just long enough to march against the system and then go back to enjoying the benefits while succumbing to the slick, green solutions put forward by the idle, privileged and ignorant.

We turn our light switch on and it works, making us confident enough to demand to shut down the nuclear reactors. We cry foul at petroleum companies as we are heating our homes with clean, natural gas. Our guts are softened by the protection from contaminants afforded by modern, plastic food packaging and then we blame the producers when we don’t manage our waste properly. Under constant pressure for industry to reduce emissions, our urban air quality continues to improve but then we just hop in our cars for short journeys around the corner.

Since we cannot seem to remember a time when we had never had these benefits, we really don’t get why we need to fight to protect them.

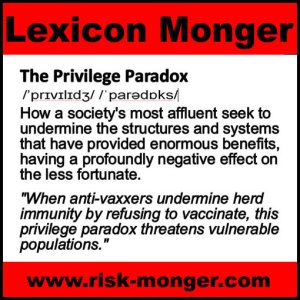

The Privilege Paradox

The more the corporation-built system works, the more we benefit from the goods and services it delivers, the less we trust it or the organisations that produced them. I would like to call this the “privilege paradox”: a phenomenon describing how a society’s most affluent seek to undermine the structures and systems that have provided enormous benefits, having a profoundly negative effect on the less fortunate.

The more the corporation-built system works, the more we benefit from the goods and services it delivers, the less we trust it or the organisations that produced them. I would like to call this the “privilege paradox”: a phenomenon describing how a society’s most affluent seek to undermine the structures and systems that have provided enormous benefits, having a profoundly negative effect on the less fortunate.

Readers of this blog know I have little patience for naturopathic gurus who have enjoyed a life of luxury and privilege and, through a sense of entitlement, feel emboldened to attack the foundations of their good fortune. They have been given wealth, health, safety, economic security and opportunities their grandparents could only have dreamt of, assume it is their right by nature, and then seek to condemn these achievements with the most paradoxical behaviour.

- With modern medicine wiping out many deadly diseases, naturopaths feel healthy enough to demand that we stop using vaccines.

- With agricultural sciences continuously increasing farm yields to meet a more affluent, growing global population, activists from the organic food lobby are pushing to remove technologies that could significantly increase agricultural output.

- With multinationals bringing increased prosperity throughout emerging economies with global trade and the free movement of goods and services, we are now seeing anti-capitalist protectionists bring their scorn onto the streets.

Whether it is in California or France, the privilege paradox is being imposed on those less fortunate via a biased media, a weak political ruling class, the rise of social media naturopathic cult gurus and a rising level of scientific ignorance. Luddites in the past were not the affluent and influential – they could be ignored. Today, it is different. Their success in diminishing public trust in the expert and the emergence of a form of blockchain trust has worried this humble blogger. I find it a social imperative that rational people fight to defend science and resist the rise of these zealots.

When I wrote my blog, I am Insignificant, in the back of my mind, I was thinking about how entitled so many people around me feel today. Professors in neighbouring classrooms often have to endure the sound of my voice thundering upon my students: “You are not special! You deserve nothing that you haven’t you, yourself, earned!”. Some of them get it … others can’t be bothered to look up from their phones.

Like many baby-boomers today, my parents grew up during the Depression, and as Ukrainian immigrants, were second class citizens in Manitoba, Canada. They knew “want” and they wanted to make sure their children did not experience that. This, in part, fuelled the post-war industriousness that allowed for the expansion of industries and consumer goods.

These ‘years of plenty’ have gone on for a very long time, thanks to the corporation. The capitalist system has worked beautifully to enable economies to grow, people to be educated and scarcity to be limited if not eliminated. For almost any problem or challenge, industry is providing solutions. The neo-Malthusians will crow that the problems are getting harder (climate change, antimicrobial resistance, obesity, over-population…) but the system is addressing these problems. For two centuries, these anachronists have been begging to prove Malthus right, but every single time, technology throws their theories back into the deep grass. Pulling the corporation out of the mix because of the rants of some ideologues would certainly worsen the situation.

Because of the dangers of the privilege paradox, I sometimes have that uncomfortable thought that it might just be a better idea to let the zealot campaign cults win and allow the entire system to fail. Let the lights go out, let the crops fail and famines rise, let the vaccines stop and allow diseases to spread, let the markets collapse and the tribes fight for scarce resources. This will lead to a generation of want that may give birth to a new generation of industriousness. But then I wake up in a cold sweat and remember what humanity is all about.

HEALTH WARNING: I would like to bring out the fighter in me now and express how I really feel about what the privileged zealots are doing. For those who think the world of academic debates should remain civil, you really should stop reading now. In the last section, I just need to get something off my chest.

You’re a Pretentious Little Bastard

So whether your name is José, Martin, Zen, Pavel, Stéphane, Gary or Carey, if you are paying your rent by spreading public distrust in the products and services corporations have given us, if you think the world would be better without their achievements and innovations, if you think getting rid of the global free-trade model will make the world better, then I have a few words for you!

Hypocrite: I find it the epitome of pure hypocrisy that people who make their coin trying to undermine the public trust in industry, technology and science are paid directly by the most unethical corporate lobby to have ever disgraced the world of public policy. The organic industry increases their market-share and bottom line by spreading fear and lies through networks of pretentious trolls and cosmopolitan zealots. Any industry lobby that concentrates on attacking and maligning its competition for profit clearly has no moral standards or ethical codes of conduct. That they can impose their quasi-religious cult rituals on such large vulnerable populations, handcuff their farmers with ridiculously unscientific standards and spread lies to try to harm the livelihoods of good people leaves me wondering whether these mercenary monsters have souls. The organic industry’s social media manipulators, lovingly engaging in a ‘bellum sacrum’, have proven to be even more lacking in ethical integrity. They’ll take money from anyone with a wallet open, including anti-vaxx lunatics, anti-Semite tractor salesmen, slimeball tort law firms and, gulp, George Soros. The high-water mark for ‘please-fund-me’ hypocrisy was having to watch Corporate Europe Observatory’s Martin Pigeon desperately trying to defend the murky transactions and lies of his dear little bought-and-paid-for scientist, Chris Portier. Disgraceful!

Ignorant: When you are presented with evidence that clearly shows how technology and trade have improved lives and you spend your time instead trying to find ways to play down the positive contributions, then you are spreading ignorance. When groups like Corporate Europe Observatory or US Right to Know look at agri-technology, they do not even bother to try to understand it. They work tirelessly to reject the science and benefits, and if it proves too hard, then they just turn to argumentum ad hominem to hopefully scare intelligence out of their narrow-minded little tribal circle. How CEO could group together and blindly attack novel and highly beneficial plant breeding techniques without using any scientific evidence is just beyond me!

Liar: I understand that zealots feel they answer to a higher calling and thus do not consider basic moral standards as something to interfere with their Machiavellian strategies (I have written about it), but that does not give them the right to lie or act beyond the laws of common decency. When you are presenting information that will lead to public fear about the food choices they make, you need to have a little bit of evidence to support it. When you capitalise on public fear of chemotherapy, and offer solutions like lemon juice and turmeric, your exculpatory clause should not prevent you from being thrown in prison. When you demand that others need to be open, honest and transparent, maybe you should be too! When you cherry-pick evidence, you are a liar.

I’ll stop here before I write something I might regret!

Reblogged this on Peddling and Scaling God and Darwin and commented:

May be big corporations aren’t that bad after all.

Perhaps you could spend a week using nothing made or sold by big corporations whether BP, ExxonMobil, Walmart/Asda, Sainsbury’s , Ford, or anyone else.

A good challenge

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Michael – it would be rather difficult to spend a day using nothing made by corporations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

David,under section “the privilege paradox” you attribute the wiping out of many deadly diseases to naturopaths !

Also,increased farm yields are attributed to activists from the organic food lobby !

The sentences need restructuring to avoid these unintended meanings.

Fine article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Barry – when I do manage to achieve brevity, I risk clarity. The master of wordiness has tried to reformulate the sentences 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great blog. I am a little curious to know what happens when you actually get mad … just a little. As a plant biologist I feel I need to clarify your fruit metaphors: When someone selectively takes a few scientific studies and ignores the overwhelming majority it is called cherry-picking, When someone does the same thing and makes a living off of it… it’s called date rape.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Wayne – I don’t think I’ll ever be able to eat dates again without thinking of that one!

LikeLiked by 1 person