See the Czech and French translations

I gave the last keynote at the IUPAC global conference on crop protection in Ghent, Belgium on 24 May 2019. The original title was: Blockchain Trust, but that morning I felt I needed to deliver a stronger message: On how 20 years of precaution had poisoned our trust in scientists and our ability to innovate and solve problems. I was speaking at an event that gathered over 1500 of the world’s leading chemists, chemical engineers and agriculture technology researchers, so I felt comfortable enough to let my guard down (and try to get them to raise their guard up). As transcripts of this speech were being prepared in other languages, I felt I needed to get the English version out, but my health and time issues have not been kind to me. I am so grateful to François Manchon who took the time to diligently transcribe my speech for the algorithm gods. I should talk less … but some things are easier said than done.

The full 35 minute speech can be found here. There are shorter clips tied to parts of the selected text. The titles are added for structural purposes.

David Zaruk’s IUPAC Speech, Ghent, Belgium: 24 May 2019 at 09:05 am

I am going to start with a story. It’s a bit strange, I’m not going to use any slides. I hope you don’t mind, I just want to talk to you for a little while.

“It’s OK papa, he’s got a great rating!”

Two years ago, I am one of those crazy people who likes to run, and like those crazy people who like to run in strange ways, I like to run up and down mountains. I was training for the Mont-Blanc Ultra and so of course it’s a bit of a challenge. My daughter wanted to come and be part of my support team. She was 21 years old at the time. I had to go up at 3000 m and keep training and get used to the oxygen levels, because here in Belgium, you know, 50 m altitude you don’t really get much air the same way. She wasn’t able to come up well in advance, but she was trying to figure out a way to get to Chamonix in a fairly reasonable way, and meet me and be part of the support group.

She couldn’t find a cheap way, but she managed to find a person, a man, who was going to be driving all night, the night before, to come up from Brussels to Chamonix. And, well, like any parent of course, I have quite an attractive young daughter, and the idea of her sitting in a car all night with a strange man didn’t seem to appeal to me. So I expressed that to her … and her attitude was: “It’s OK papa, he’s got a great rating!”

What???

We today trust and we would get into a car with a strange man and drive all night across Europe because somebody else gave him a great rating. My Uber driver who took me here this morning has had over 5000 five-star ratings. I liked him already even before I got into the car!

The Blockchain Model of Trust

What is happening today is that we have another model of trust. We have to understand that. When we go to the cinema, we don’t listen to what the film producers say about it or what the film reviewers or critics say anymore. We listen to what our friends say. We will rent out our sofa-beds to complete strangers according to the ratings we have. Everybody now is going around rating everyone else. When you got into the hotel you checked the ratings to see what people like you were saying.

So this is the “blockchain” in action. I know some of you are perhaps mathematicians and you know very well what the blockchain is, you know it’s not exactly that because there are still people involved trying to sell you an app. But it’s more or less the situation as everybody now, peers, are rating everyone else. It’s why transparency is so important for us today, because with transparency we expect that every rating is true. Uber lost its right to operate in London because they did not declare two cases of sexual abuse in their cars. Automatically: not transparent? It must stop.

We were talking yesterday about the importance of transparency. We can see it’s important because of the “blockchain”. But how does this work? If we are no longer trusting the expert, we are no longer trusting the authority, we are now trusting people like us, people from our tribe. People who are able to say “I agree this is safe” or “I support this”. This is something different and I think we have to be aware that this is tied very much to the communications revolution that we have today. We are no longer relying on the authorities. How does that work?

Google Wants to be my Friend

Today we are finding ourselves communicating not as part of society, but as part of our tribe. Once again, the algorithms and the “blockchain” have determined more or less where our tribe is. Stop and think for a moment of a simple search. Whenever I feel vulnerable, I don’t understand something, I go to my friend Google. I will go to Google and I will ask a question. The question might be something like “Will vaccines give my child autism?”

Now, Google is not going to try to educate me. Google wants to be my friend, so Google is going to send me to a site that Google understands I want to go to, and that is based on all of the past searches that I have done. It is based on the types of people I associate with. It is based on that whole system that the algorithms of my last search histories will say “This is where David wants to go”. Google is not going to say: “Don’t be stupid, vaccinate your children!” If I am vulnerable, and that’s why I am searching on Google, because I don’t understand something, I need something I can trust. Google is going to send me where Google thinks, or the algorithms think, I will find the answer I’m most happy with.

By the way, has anybody here ever checked for spelling a word in Google? Yes, so what happens? Does Google say: “You’re wrong” or will it ask: “Did you mean this?” It took me ten minutes one time to realize I was misspelling a word because Google didn’t say “Don’t be stupid David, learn how to spell the word”! Because Google does not want to tell me that. Google wants to be my friend.

I will then be put into a tribe with other people who think like me. I may be very concerned about vaccinating my children and I will find other people who are also concerned and they will tell me: “It’s OK David, I understand; there are other ways; you don’t have to vaccinate.” and I will feel good, I will feel trust. I won’t have good advice perhaps, but we have to understand that this is how the trust mechanisms are working today.

The Science Tribe

Now, I am speaking to a room full of experts. A room full of scientists. How many of you have PhDs in chemistry? OK, let me do it more easily: How many don’t have a PhD in chemistry? I worked fifteen years for a chemical company and I know very well that I felt inferior because my PhD wasn’t in chemistry. The point was you are part of a community. This is a tribe. And you think very well like people think elsewhere.

Another question maybe I should ask you: How many of you buy lottery tickets? OK, I’ll repeat the question because I don’t see any hands … How many of you buy lottery tickets? One person, OK. I’m going to talk to you at the break Sir, because somehow, you’re in the wrong building!

This is one of the difficulties: you think in the same way as the people around you. I’ve got news for you; most people don’t think like you. Somebody is out there buying lottery tickets. I mean most people out there are numerically illiterate. (I found out yesterday we are arrogant, by the way, I am trying to figure that one out still… we were talking about that last night.) That idea that people are numerically illiterate: they will buy a lottery ticket to pay off their credit card debt. It is how most people are thinking. That is how the marketing world works.

But how is that compared to your own tribe, then? Your idea is quite simple: there are facts out there, you have done the research, you understand it, and you have a solution. That is, I think, a rather narrow limited tribe of people compared to the large general population. Until recently that was not a problem, because we relied on the experts, and the experts were the people who knew these things, and we asked the experts. But as I said, with the “blockchain” model of trust today, we are no longer asking the experts. We are asking the people in our tribe. Google is telling us what we need for our decisions.

We Can’t Trust the Experts

So you begin to realize that’s not really a problem because the regulators will solve these things. The regulators will manage these things. You may have noticed in the last couple years a trend to reform that process. It is not democratic. (Nobody ever said science was democratic, did they?) Well, that’s the problem today. So, what happens then? Well, we have another issue and that is that these people in the tribes are growing.

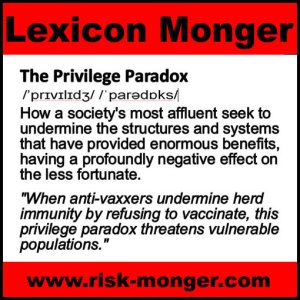

I have my own tribe. I do a blog called The Risk-Monger. I like to think my tribe is quite active. I generally fight with them quite a bit. It’s only about ten thousand people. This may seem like a lot, but Jamie Oliver has about ten million, so, when Jamie Oliver tells you that something organic is better, his tribe hears that a lot louder than any voice I can have. Probably a lot louder than any voice in this room (although I understand now from the speaker before that if you eat organic you can put yourself in some dangerous situations, but anyway I’m not going to touch that…). The point quite simply is my tribe is quite small.

And the experts are no longer considered valid. We cannot trust the experts. Apparently there is a company that no longer exists, that begins with an M. They apparently went and paid all the experts. They paid all the scientists. They paid… hands up everyone that has been paid by that company that begins with an M… well apparently … They say it a million times so it must be true!

The point is we cannot trust risk assessments anymore. We have to change the risk assessment process now. Well what do we change it to? We cannot trust the experts, but we trust the “blockchain”. We trust people like us. What do you mean? Well, we’ll have citizen panels. The citizen panels will decide whether or not something should be used or not. Makes sense, right? We are all in the same democratic situation, I mean we talked about that on Monday night: that if the public wants it, if the public wants a new technology in their phone, who is the regulator to stop it? We’ll just give it to them.

We Trust Citizen Panels

And so we have to understand how a citizen panel will work. They are not experts. How can we have a good rational decision about public safety, public health if these people on citizen panels buy lottery tickets to pay off their credit card debt? That does not make sense. Well, until you understand what the motives of the people who want those citizen panels are: it is not to improve technology, it is not to improve discovery, it is not to advance science to improve public health; … The motive is to stop it.

And so if your goal is to stop the technology, stop the development, stop these things because they are causing climate change or something else, then you have got to understand it from another point: the precautionary principle has been the tool they have been insisting on. The precautionary principle is not how to lead to better technology. It is how to stop things that we are uncertain about.

And so a citizen panel’s job is very simple. “Are you certain that this product is safe?” Two emotional concepts I can’t really begin to define right there: certainty and safety. And of course, the scientist would say: You know, certainty to a certain degree, it depends on the context… “No? … So you are not certain? Get rid of it!” … “Can you guarantee this is not an endocrine disrupter?” Er, … well, compared to other products that we are using every day… “No… you can’t? Then get rid of it!” So we are beginning to see suddenly that the precautionary principle is a very useful tool, because all you have to do, like a baby, is say: “No. Come back when you are certain!” which I think most people in this room will know (certainty) is not really an important point.

The Precautionary Logic

But there is something else about precaution which is interesting and that is something that I want to talk to you about. It is a different type of logic.

I have my bag. I didn’t know where to put it so I hid it behind here. Sorry Femi. I brought an umbrella today. It is in my bag, it is always in my bag. I live in Belgium so when I can do this exercise and it works, it is very rare, but anyway… humour me… (Opening the umbrella) I know it is bad luck, right, but you guys don’t buy lottery tickets anyway, you are scientists, so you should understand…

Was I right? … (Photographers love this by the way, it’s my Mary Poppins moment). Was I right to bring my umbrella today? For those who don’t know because we are in a dark hall, it is a beautiful sunny day outside. No, I wasn’t right to bring my umbrella. Was I wrong to bring my umbrella? No. I will bring it tomorrow, even if the forecast tomorrow is for another bright sunny day, I will bring my umbrella. This is a precautionary measure. Now the thing about that, and it is important to realize, is that with precaution, not being right is not the same as being wrong. With precaution you are never wrong, … just really, really not right sometimes.

So that is the precautionary logic – it is not a question of right or wrong. Now you have to see it from your own view, from a scientific logic. If I am right, I am right. If I am wrong, I am wrong. Precaution is not the same: not being right does not mean you are wrong. You are just being careful, being safe. Better safe than sorry.

Now, one of the problems that many people have in this room is that if they think they are right, they then think they have the right. And that gets us into a lot of issues because people may understand that you are right, may understand that it is safe, but then say: “No, thank you, I don’t want this technology.” – But it is going to save lives! – “Phhh! Not my problem.” And so you have to understand we are dealing with another type of logic here, and that is where we are getting into challenges.

When we speak in these terms, and we understand the terms of trust are different, we begin to see that the world that you probably understood when you were doing your studies has changed. And are you ready for those changes?

The Poison of Precaution

Well, precaution has done something more diabolical than that, I am afraid. This gets rather hard to speak about. I have got a piece, well I hope to finish this piece someday. It has been on my computer for about six months. Essentially one of the problems of precaution, more than anything else, [is the mindset] (at least the version of precaution that we are now celebrating the twentieth anniversary of next year, which is the David Gee version).

David Gee wrote “Late Lessons from Early Warnings”, and his definition of precaution is a reversal of the burden of proof. Until you can prove that this technology is safe (once again: certainty? safety? … good luck…), you cannot have it approved. Once again these citizen panels, now, have no problem removing this. So, science is guilty until proven innocent with any new technology. What does this mean? Well, after twenty years of applying this mentality we are beginning to see that your world, the discoveries you may have, the developments and solutions you may provide for society … they are not welcome.

In fact if you look at precaution today, the idea of precaution is: We have to stop doing things that we have been doing. The people on the streets for the Extinction Rebellion are not saying “Help us, science, we need science to solve the problems. We need science to create new discoveries, to help us find solutions.” They are not saying that. They are saying “Stop flying, stop eating meat, stop industry, stop banking!” Their view is: take a precautionary approach. In our own field, if we talk about weed resistance to herbicides, the solution is “Stop using herbicides; you are using too many herbicides, that is why we have to stop”.

Probably the biggest crisis we have today facing humanity is antimicrobial resistance. So the solution: not to develop new discoveries, find new solutions to help save humanity because we are facing a super-bug that is going to wipe us out? No, the solution after twenty years of precaution is quite simple: stop using antibiotics. So we have now this precautionary logic morphed into a precautionary mentality which is the same as saying: scientists are not going to provide the solution; scientists created the problems.

Your Solutions are not Welcome

Somewhere in this room I am sure there is another Fraser Stoddart. There is another potential Nobel laureate. You have got the greatest minds in this room who would be able to solve something like antimicrobial resistance, be able to create that new herbicide that is going to allow farmers to continue. But there is nobody who is going to allow you to continue because the view is quite simple: we need citizen panels to stop these things; we need governments now to solve these problems.

Little Greta is sitting outside of the Swedish parliament because she wants the government to solve the problems. She does not want industry to find a new technology. This is the problem we have today: the people who are complaining want a new government led by citizens panels to get everyone to stop doing what was causing, in their views, the problems. It’s not really the solutions I believe you were trained for. And I am pretty sure that the solutions that are in this room should be allowed to go forward. And that’s a real problem.

A Personal Story

Let me give you another story and I am going to wrap up with this. Last year again I was training for the Mont-Blanc (I don’t know why I keep doing these things, but anyway…). It was in July and I was doing the usual. I was in good shape. A lot better than I am now by the way. One day I woke up, after what was a pretty good training run, and I did not feel that well. The next day I woke up and I could not walk. Now imagine an ultra-runner who could not walk, OK? Just emotionally…

It was sudden. I was misdiagnosed as having a herniated disc, and for about two months I was suffering excruciating pain, night drenching… Essentially what I had was quite a severe infection. That was in July. For eight months I was battling the infection, and the whole point was I tried five different courses of antibiotics. Finally one seemed to work. My doctor said quite simply: “You know David, that would have killed a normal person; you were lucky you were in good shape.” And all my friends were saying: “You got that infection by running up mountains, you idiot”.

But the whole point is we are more and more facing vulnerabilities today. We are more and more having this problem that the medicines and technologies that were developed 30-40 years ago (and the case of antibiotics is even worse, I don’t think there are any new products in the pipeline in phase III testing at the moment) and the only solution that we are given is: no more antibiotics. So we have to understand it from a point that the scientific approach is not working because we are not giving the scientists the opportunities to go out and discover and to develop these products. The precautionary cancer is spreading.

So I was lucky. I was strong enough. Normally people will get infections after an operation. And we speak about how people die: when we say somebody died of pneumonia, they did not die of pneumonia. They died because no antibiotics were working to prevent it. We have to understand how many people are actually dying from these issues.

What you Have to Do

So, what you have to do, and I will leave you with this thought, is you have to stop being in the lab dealing with the solutions, because the solutions you develop in the lab are not going to get out of the lab. You have the means. I am sure there is the means in this room, with the number of PhDs, the number of brilliant chemists in this room, there are people who are going to be able to solve these problems. But the culture out there, the “blockchain” culture, which is basically not trusting anyone they don’t understand, and wanting to move to a precautionary basis of getting rid of everything that they feel was a problem, means that these solutions may not get out.

You have to leave the lab for the lobby. The farmers have to leave the land for the lobby. You have to start standing up for science, for the chance to solve the problems. You cannot continue to take the point “Well, OK, they are not going to let us do this, so never mind”. Two more good years, or three more good years with your product on the market is not a solution. It is basically saying that we are simply letting the solutions go away.

I am going to keep fighting as much as I can for the chance for scientists to be able to discover, for scientists to be able to have these solutions. That is important for me and I want you to join me, because there are not enough people doing that.

Two weeks ago, the pain came back. The infection is back, and there are no other antibiotics for me. I need you to be able to find something for me.

Thank you.

Q&A

Host: David, thank you. When did you decide that this keynote was the right one for this conference?

DZ: This morning! It’s the nice thing about not having slides. You can decide on the mood. You can decide in the room.

Host: What did you… please put the lights up. You know the drill because we’ve got a couple of minutes with David, and I know people like to talk to him. I felt that was such a wide ranging keynote, that they can ask you many different things. So, feel free to do that? When you hear that tap on the top of the microphone I know you are ready. This is so I can actually look at David here.

You were here all this week, or most of this week. So you were picking up on conversations that people were really caring about, and then you put the keynote together, and then you picked up on those points. One of them was how scientists communicate, and the image that scientists can have, and you wove that into your keynote. Can you unpack that a little bit more because it sounded like you disagreed with the idea that scientists were probably not the most approachable?

DZ: Well, I mean it was quite funny to have this conversation that you were having last night. It was almost like everyone thought scientists were arrogant. I don’t think scientists are arrogant. I think the idea is they are used to communicating with each other and they don’t have the patience sometimes to explain to somebody else. And the vaccine story is a good example. When someone who says “Well, I am thinking of not vaccinating my child”… people start to panic, and there’s a “Don’t be stupid! Vaccinate!” reaction. And of course that doesn’t work if somebody is feeling a sense of vulnerability. And I am not saying as scientists you have to go and hug your sister-in-law to make sure she’s going to vaccinate your niece. But at the same time I think there is a sense that we have to understand that not everybody thinks the same way. And not everyone is willing to listen.

Man from the audience: Good morning David. Two things: First of all, the lottery I am playing is supporting social activities in the community.

DZ (laughing): You’re forgiven!

Man: The second thing is why people are requesting 100% safety from crop protection is because are not aware of the benefits of it. People are accepting the risk of drinking alcohol, driving cars, flying planes, do whatever, sports, running up mountains, because they think it’s good for them and they are willing to take the risk. In crop protection they just see that it is possible to do everything in organic, at least from their perspective, and so they ask themselves: “Why isn’t it done?” And they think it’s all about bad corporate, big companies wanting to earn money?

DZ: Indeed the story and the narrative that is painted by a lot of people and I know quite a few people in groups like Corporate Europe Observatory, they all smoke and drink, but they’ll talk about organic … in fact for a lot of young people it’s the same thing. There is a contradiction quite simply, a person may take a cigarette or a drink because they feel they are in control. It’s their decision. A good part of risk perception is agency: if I am in control and I am used to, it’s familiar and I trust it. I am not in control of what happens to my food if I feel that there is something going on. And of course, there are a large number of organizations that benefit and profit from Project Fear. It’s a danger I think in a lot of marketing circles to see how people play this game, to create a luxury product which they can then retail at a higher price. It’s affecting farmers. It’s a sad situation I think, all around.

Another man from the audience: Hi David. You are Canadian, right? And yet you know the corridors of power in Brussels pretty well.

DZ: They know me!

Man: They know you, right. How much of what you describe would you say is actually more typical European, or Brussels bubble, or is this a global trend? Is there an element of inward-looking nature from Europe? I just want to see how much of what your idea is. Is Europe setting a trend for the globe to follow? Or is there a potential for a counter move where at some point in time actually the rest of the world will continue, with or without Europe?

DZ: That is a hard question to answer. I think one of the things I find is that Europe has been placed in the handcuffs not of precaution, but the Sustainable Use Directive with the hazard-based approach. If you were to ask any regulator what they feel about this, they would say… “I can’t … Phhh! … but this is all we have. We can’t do anything else.”

That has created an interest for people across the world. I refer to the people coming from the US to campaign against glyphosate to ban GMOs in the US as carpetbaggers, because it is much easier for them to affect the policy in Brussels than it is in Washington. So, we are not facing simply just some French peasants’ associations who don’t want CRISPR. We are facing a large global body that figured that if we can ban it in Europe, we can stop trade, and that’s a much more effective way. Now, that’s a cynical approach to say that, but there are a lot of activists, for whom, simply it is all about winning. They don’t care about facts. They don’t care about nature. I mean the Green Party that wants to ban nuclear does not care about the climate. The people who want to ban glyphosate don’t care about conservation agriculture and soil management. That’s a religion and they are coming to Brussels to preach their religion now because the precautionary principle makes that easy. Sorry, it’s a dark answer.

Woman from the audience: Yes, it is. The theme of scientists becoming better communicators with non-scientists has been discussed this week quite a bit. And so I guess my question is with regards to what is the most effective way of doing that? You know, in the past I always thought well, in order for us to be able to communicate you have to have at least the same platform, you know, so get the level of education up to a certain level so they understand the things that we are trying to communicate. But I don’t think that’s really effective. At least it has not been my personal opinion. And then I veer towards just, kind of a cop out, when they ask what do you do for a living? I say I am an organic chemist. I didn’t lie, right? But that does not really solve the problem either. That’s me just taking advantage of their misconceptions. So, what is the most effective way for a scientist to communicate with non-scientists?

DZ: This is one of the things I have been working on this for more than two decades now. I have to say I like to consider myself a [communications] researcher because I am always testing out different things. With the advent of social media you begin to realize that scientists can reach out to their sisters-in-law. They can reach out to the regulators. They can reach out to the consumers. But what I am also curious about is whether they do or not.

Just to give you an example. I created an experiment recently for the European Parliamentary elections where it’s quite horrifying when you look of the level of science illiteracy that’s going on in the European Parliament over the last five years. So, I wrote something called the Science Charter and many scientists agreed right away: I mean ten little steps that every MEP candidate should commit to. The logic was very simple: I want you to be able to send this Charter, this little image, this meme, to every person in your area who is running, to put science back onto the debate, and let the communities and the tribes have this discussion about science, rather than have it about immigration or glyphosate, as a means to decide who your next MEP is going to be. Scientists thought this was great. I had it translated voluntarily into ten languages on the first weekend and I was promoting it. But the scientists are not going to the next step. They are not.

Just to give you an example. I created an experiment recently for the European Parliamentary elections where it’s quite horrifying when you look of the level of science illiteracy that’s going on in the European Parliament over the last five years. So, I wrote something called the Science Charter and many scientists agreed right away: I mean ten little steps that every MEP candidate should commit to. The logic was very simple: I want you to be able to send this Charter, this little image, this meme, to every person in your area who is running, to put science back onto the debate, and let the communities and the tribes have this discussion about science, rather than have it about immigration or glyphosate, as a means to decide who your next MEP is going to be. Scientists thought this was great. I had it translated voluntarily into ten languages on the first weekend and I was promoting it. But the scientists are not going to the next step. They are not.

I thought that 3% of the European population would be enough to create a scientific discussion that could control and, in a sense, dominate the issue for the next European Parliament election. But the scientists have to do the next step, which is to step up, and that’s the harder part. So I am experimenting, I am testing, I am researching, so now the next point is: we know logically it’s possible. How do we get out of the lab and into the lobby, or off the land and into the lobby? How do you get your voice heard?

Host: David, that is a really good segway into Nathan’s question: Do you think we can increase the crop protection tribe, and if so how?

DZ: Well, we are having fewer farmers, and as we have been discussing this week, we are no longer having our grandparents as farmers. People are no longer in touch with the farm and that’s one of the real challenges. I can remember I went on a speaking tour among farms in Southern England for a week. It was fantastic. I had a great time. I was trying to get farmers to use twitter more, to be able to get involved and to communicate because people love the story of farming. Everyone is interested to know where their food comes from. A farmer who can simply, from his combine, show what he’s doing … people are interested in that. So I kept the same message, a bit of a stump speech all week, and I can remember one farmer saying “Well that’s good … that means I have to get a computer”… So we’ve got to find a way to get the farmers to communicate more. There are some very good farmers out there.

Host: Just get a really nice phone.

DZ: Exactly. The idea is we have to get the farmers to tell their story more. This is really one of the good news stories, that we are able to feed the world with fewer inputs, fewer people, less land, more yield. The people who want the opposite, because of some ideological, cultist religion, have to understand that these famers are not doing this because they hate nature or hate the public. In fact they are feeding their food to their kids.

DZ: Exactly. The idea is we have to get the farmers to tell their story more. This is really one of the good news stories, that we are able to feed the world with fewer inputs, fewer people, less land, more yield. The people who want the opposite, because of some ideological, cultist religion, have to understand that these famers are not doing this because they hate nature or hate the public. In fact they are feeding their food to their kids.

Host: You told part of your story this morning. It is very personal. A lot of people would be quite surprised to hear that. Tell us how you are right now.

DZ: I am in pain. It hurts.

Host: You asked people to help you, but how do they actually help you?

DZ: We have to stop thinking that the age of affluence means that we are all OK. Right now we are able to ban all these substances because we are comfortable enough to feed ourselves. We can still remove a lot of the technologies because there is something else that we can still use. We don’t think about developing countries where they are not in that situation. We are even assuming for example that Africans can do better without agro-technology. We assume that everything is like that because we are so lucky. We are so close – this age of affluence and well-being, and we are living longer – we are so close to having this turned upside-down. It just takes a few stupid things by a few stupid people (sorry…) to put us back.

DZ: We have to stop thinking that the age of affluence means that we are all OK. Right now we are able to ban all these substances because we are comfortable enough to feed ourselves. We can still remove a lot of the technologies because there is something else that we can still use. We don’t think about developing countries where they are not in that situation. We are even assuming for example that Africans can do better without agro-technology. We assume that everything is like that because we are so lucky. We are so close – this age of affluence and well-being, and we are living longer – we are so close to having this turned upside-down. It just takes a few stupid things by a few stupid people (sorry…) to put us back.

And I know very well how vulnerable we are. We are facing, particularly with antimicrobial resistance, what I am fighting, it is not a sexy disease, but I know the pain and suffering. I know what it causes, and when I find somebody else, because I am in hospitals a lot, when I find somebody else, I ask them “What is your pain scale today?” because pain killers don’t work either. And it is not something that we can just sit back and say “It will be all right Femi”. It is not going to be all right. We are not in a situation where we can just let precaution take over and give up on scientific discovery and development.

(Applause)

Host: It is not really a pain killer, but it does make you feel good. Chocolate, David!

DZ: Thank you so much.

Host: I am thinking that, come the break, I don’t know if you are touchy feely, you are going to get a few hugs. David, thank you so much.

-End-

4 Comments Add yours