To put an end to the fear campaigns that have promoted a corrupt organic food marketing concept and stop the endless series of regulatory restrictions imposed on farmers and researchers, we need to rethink farming’s strategy and how the food chain cooperates and coordinates. If not, farming decisions will continue to be influenced by activists, food yields will decline giving rise to more hardship for farming communities, and food insecurity and malnutrition among vulnerable populations will return once again (but at a time with population increases and added climatic stresses). Perhaps it is time for a “Better Farming Initiative”.

What follows is a reprint of a three-part series I wrote this year in my Risk Corner Column for European Seed. The first segment looks at how the use of the marketing term “organic”, with so many meanings and interpretations, still continues to rise in popularity at the regulatory and (affluent) consumer level. Given the unsustainability and potential threats to food security from the organic food production approach, the second part takes the Better Cotton Initiative as a benchmark to move away from the “good versus evil” binary farming narrative imposed by the environmental activists and adopt a “sustainable farming first” approach. But in order to remove the organic restraints on the food sector and develop such a Better Farming Initiative, the food value chain (from seed breeder to farmer to retailer) will have to integrate its production, research and communications strategies.

The original articles are available here: Part 1 (in Dutch), Part 2 (in Dutch) and Part 3 (in Dutch).

1 – 50 Shades of Green

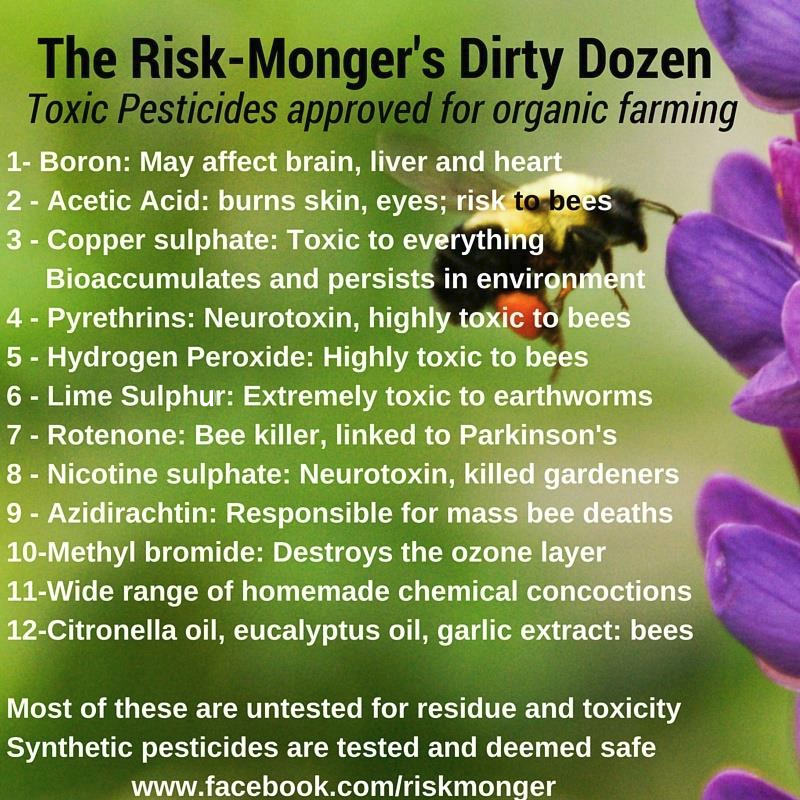

When the “Risk-Monger’s Dirty Dozen” list of pesticides used in organic farming was published, I had broken a taboo. Before that 2015 article, most people assumed ‘organic’ meant completely ‘pesticide-free’. Today the word organic has become much more elastic as markets increase, new technologies challenge organic farming practices, and a public has become more concerned about purpose-built food.

The organic food lobby responded to the attention drawn to their big lie with more wordplay and deception, claiming now that organic food is not grown with any “synthetic” pesticides or that organic farmers don’t use “toxic chemicals”. When confronted with the use of some very hazardous organic pesticides like copper sulphate or neem oil, they claim that farmers are only allowed to use small amounts and only when necessary. In some countries, organic farmers are also permitted to use certain synthetic pesticides (if the organic-approved ones are not efficient). But there are thresholds to maintain to still call their produce “organic”.

To aggravate the situation, each country has its own standards and tolerances for what is needed to fulfil the “organic” certification and are not easily forthcoming on sharing their preconditions (which evolve quite frequently). International organic food lobby groups like IFOAM don’t clearly define acceptable practices, whether it be on pesticides, seeds, fertilisers or growing methods.

So, what does organic mean and to whom?

Traditionalists

From permaculture to biodynamics, a traditional organic farmer starts with soil health as fundamental, seeking approaches to reduce fertilisers and increase biodiversity. The term ‘regenerative agriculture’ was promoted by the Organic Consumers Association, but this term has now been adopted by conventional farmers practising conservation agriculture (no-till farming with complex cover crops terminated with herbicides). While soil health is the main concern for all farmers, many traditional farmers define ‘organic’ solely by doing what benefits the soil (naturally). “Soil is the source of life!”

A few years back, organic purists were outraged that the USDA allowed hydroponic-grown food to be labelled as organic (bioponics). These are not just grown without soil; they tend to consume large volumes of liquid fertilisers and energy. While increasing yields without pesticides, hydroponic farms are also often large, capital-intensive operations. Many of the emerging vertical farming operations tick all of the boxes for sustainable agriculture in urban environments, but they also tick off most organic traditionalists.

Technologists

Perhaps the greatest failure for the organic movement was the missed opportunity to allow several of the new plant breeding techniques for organic seed development. There was open debate in 2015 about the benefits of NPBTs until anti-industry activists in IFOAM, OCA and Corporate Europe Observatory shut down the idea. The radical gardeners in the organic lobby considered this as “GMOs through the back door”, not natural and driven by patents. While I struggle with their definition of a natural seed, this discussion showed how the hardliners see technology merely as biotech (and unwelcome). This failure to allow science to support nature was a fatal blow to organic agriculture’s ability to be competitive and sustainable.

As technology advances in fields like precision farming and robotics, will the traditionalists continue to obstruct solutions that would help organic farmers achieve their goals while making a living? This (younger) part of the movement will have to speak louder if they are ever to secure a future for organic farming.

Agroecologists

Many in the organic lobby have pinned their colours onto the agroecology mast. While there are many definitions and standards for agroecology (including some non-organic techniques), the reactions against large, intensive farming, corporate involvement and the globalisation of the food chain has defined it mainly as a social justice movement. The call for social justice in developing countries includes a plea to promote organic practices among smallholders and subsistence farmers. Given that most poor smallholders are organic by default, the only thing the agroecology/organic movement is doing is giving a small amount of funding and advice without the means to lift peasant farmers out of poverty. Agroecology here is more of a political ideology of agriculture, with many well-known activists like Vandana Shiva claiming it as their own. It adds a political dimension to the radical organic wing (while impoverishing farmers).

Pioneers

There are some third or fourth generation farmers, often driven by market opportunities, who can afford to partially rotate into large-scale organic production, find or innovate on organic methods while developing best practices for the next generation of farming. They are using emerging technologies, combining planting approaches and taking risks. Conventional farmers are looking over the hedge with curiosity. Driven by discovery rather than ideology or labels, these pioneers are the one hope for the future of organic agriculture.

Time for a change

As the term “organic” is merely a marketing tool, carrying no real added value to consumer health or the environment, we need to rethink how food production is considered. There are some organic practices that are beneficial, but there are also conventional technologies and synthetic substances that better improve yields and protect the environment. With the challenges facing agriculture, we need pragmatism and ingenuity, not blind, cultish ideology and fear-driven marketing campaigns. My next column will look at an alternative to this organic/conventional polarity by introducing a concept called “better farming”.

2 – The Better Farming Initiative

Due to successful fear-based marketing campaigns, the demand for organic food in many affluent countries is rising far faster than yield capacity, dangerously stressing global food security and land use practices. We need a rethink: away from this binary organic vs conventional/good vs evil dichotomy and towards holistically promoting better farming practices.

The Better Cotton Initiative

In the mid-2000s, there was a sharp increase in demand for “organic cotton”. As it was impossible to fulfil this demand without imposing a terrible cost on farmers and the environment, stakeholders got together and established the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) in an attempt to break the binary organic/conventional chains threatening the entire market. The BCI is a series of principles and standards to ensure that the cotton was grown, harvested and manufactured in the most sustainable manner possible. As a label, it commits to continuously developing best practices and managing risks responsibly. Ten years after its launch, 20% of all cotton is BCI certified.

This pragmatic approach broke the handcuffs the organic label was putting on cotton farmers, with the supply chain supporting agricultural improvements and better working conditions for farmers while increasing consumer trust in agricultural stewardship.

Isn’t it time for such an initiative to be extended to all farming sectors? Isn’t it time for a Better Farming Initiative (BFI)?

The Benefits of a Better Farming Initiative

Better Farming principles would promote sustainable agriculture outside of any organic vs conventional agriculture preconditions. For example:

- The non-scientific dichotomy between synthetic and natural-based pesticides would be eliminated. Each substance would be assessed according to its sustainability profile.

- Seed breeding technologies would be evaluated on their merits rather than some arbitrary process definition.

- Any BFI would have a key goal of enhancing soil management. This is not a one-size-fits-all approach, but the objective should be to continually work for better soil health, carbon sequestration and reduced erosion and degradation.

- Smallholders in developing countries should be offered the best available tools to increase yields, reduce harsh working conditions and bring their produce more easily to market. We need to stop imposing ideologies that impoverish the most vulnerable.

- Assuming farmers can increase yields on more fertile land, the BFI would encourage means to return less productive land to biodiverse usage.

The BFI would concentrate on developing more climate-friendly farming techniques, resilience, better labour standards, fair trade and access to markets, data and technology. This Better Farming approach can also benchmark excellent national initiatives (like the UK’s Voluntary Initiative).

Integrated Pest Management’s Expectations

Many of the recent attacks on crop protection tools were not due to actual environmental risks, but over how their use confronted certain activist expectations: that Integrated Pest Management (IPM) was intended to move towards eliminating all pesticide use. So, while herbicide-resistant seeds may reduce overall herbicide use (and allow for much better regenerative soil management techniques), it also implied that herbicide usage would not be phased out. The campaigns to ban certain neonicotinoid-treated seeds was never about saving the bees (many alternatives were far worse for pollinator health). By treating seeds to prevent any possible pest infestation, these neonics went against IPM’s “use only when necessary” ideal (regardless of the reduced overall environmental toll).

IPM would not achieve the activist ideal if these pesticides were promoted for their sustainable solutions so opponents launched intense campaigns (resulting in worse environmental degradation). Under a Better Farming standard, these crop protection technologies would be promoted as best available soil and pest reduction practices. BFI would entail a more reasonable, pragmatic interpretation of IPM.

Better Ideas

Shifting to a Better Farming focus is urgent. Years of relentless fear campaigns have destroyed the reputation of agriculture, but a BFI would also have challenges.

Some would argue that a BFI label would be insulting to farmers (and I understand that). All farmers do the best they can to protect their soil, grow safe food and feed their communities. Sadly, the organic food industry lobby has destroyed that perception with their good vs evil mindset. Confidence needs to be restored while those struggling to meet certain sustainability standards, particularly in vulnerable regions, will need more technological support (rather than more ideology).

Some would argue the Better Cotton model is impractical given the disparities in the food value chain compared to the more closed cotton chain (and I understand that). The downstream food industry is going to have to step up and work with farmers and scientists first rather than immediately reacting to any consumer fear campaigns. For that we need to develop an “integrated risk management process” for the entire food value chain.

3 – Towards an Integrated Food Chain

Have you ever noticed how most food decisions are made in isolation? Retailers make product commitments based on marketing advice; farmers develop cover crop approaches with old technologies; scientists propose solutions the brands are not interested in; and the European Commission launched a Farm2Fork strategy aiming to phase out most crop protection tools … without consulting farmers.

The European Commission’s 2000 White Paper on Food Safety required an integrated approach to risk management. Our food chain should be an integrated web of communication and coordination, from seed researchers to farmers to agronomists to processing, packaging and branding actors to logistics, distribution and retail to consumers. In a perfect world, scientists would coordinate with farmers, processors and brands, retailers would consult up the chain before making decisions and consumers and policymakers would be aware of the complex process that allowed them to enjoy safe, abundant food.

But these messages are not integrated. There is no holistic approach to food chain management. Every actor represents their interest and coordinates only when it is in their interest.

With little coordination or communication among the various actors in the food chain, NGO activists and organic food industry lobbyists can freely impose fear campaigns on consumers and retailers, pressure policymakers and create structural impediments on the rest of the chain. Farmers don’t understand why politicians, activists and consumers are so worked up about a relatively benign herbicide. Scientists are baffled over the rejection of certain seed-breeding techniques.

As consumers grow more isolated from farmers (thinking a harvest is like clicking on Farmville) and policymakers continue to randomly remove agricultural technologies, something is going to give. Without proper communication and coordination among the actors throughout the food chain, without an integrated risk management approach and without shared commitments towards scientific best practices, we are risking significant crop losses, environmental decline, potential famines and global food insecurity.

Can we have a ‘Better Farming Initiative’ if brands and retailers solely seek opportunities in lucrative, niche markets? How will new plant breeding techniques help farmers grow more sustainably when environmental activists and social justice agroecologists demand only traditional agricultural practices? How will trust in food safety strengthen when so many opportunists are making false claims at different, isolated links in the food chain (largely left unanswered)?

It is time for the food chain (from scientists to farmers to brands to retailers) to tighten the links, communicate together, coordinate strategies and promote best practices. Each stakeholder in the chain needs to be aware of how their interests are integrated.

Some tips to integrate the food and agriculture chain:

- Stop allowing food issues to be considered in isolation. Retailers and brands, for example, need to speak up if farmers are denied an important technology.

- Coordinate seamlessly along the chain. Consumers perceive that their food comes directly from the farmer so any disruption in the message will undermine trust.

- Stress how innovation at every link in the chain is essential for sustainable agriculture. Seed breeders, for example, should work with farmers to develop better cover crop species.

- Limit how marketing managers can influence food production and research solutions. The food chain starts with the seed (not the brand).

- Improve the integration process by bringing together the various research communities. Universities need to develop horizontal, inter-faculty study programmes.

A Better Farming Initiative will only come about if there is better coordination and dialogue across the value chain. Retailers will not be able to feed their communities with niche, luxury products. Farmers will not be able to grow abundant yields without agricultural technologies. Researchers will not be able to develop innovative solutions without consumer buy-in. We need to abandon our silos, bust the bubbles and present a clear, shared message.

There is one fully integrated food chain, where each link coordinates with the others, where messages are clearly communicated and where consumers trust the product. This is the organic food chain and as much as their policies are a threat to sustainable agriculture and food security, they are the fastest growing segment in the market.

When the Better Cotton Initiative coordinated their entire value chain, market demand for organic cotton fell substantially. What would happen if the conventional food chain took a similar integrated approach?

3 Comments Add yours