Part 2 of the Wish List for the Next European Commission

In Part 1 of my Wish List for the Next European Commission, I recognised that the EU’s Better Regulation legislation was a failed attempt at improving governance. I concluded that there needed to be a root and branch analysis of the risk management process. A White Paper, that conceptually analyses policy options and methodologies, would be a much-needed starting point.

Risk management is core to the art of governance. In protecting citizens from harm, in solving problems and providing social goods, regulators need to reframe their profession within a bigger picture (than merely occupying a functionary position with ambitions of promotion). All societal goods involve some risk trade-off (someone needs to pay for someone else’s benefit). What regulators need to ensure is that the systems in place provide these goods without undue harm (exposures to hazards) with the objective of continually improving the beneficial goods available while reducing the risks.

Recently government policies in EU Member States have failed to meet these objectives. They have come to believe that governance is the implementation of ideals rather than protecting and enabling societal goods. And in pursuit of their ideologies, be it a Green Deal that promotes degrowth, a just economy built on equality or peace through strength, they are failing to protect or advance societal goods. They are driven by righteousness rather than rationality, idealism rather than pragmatism, and dignity rather than dialogue.

European public access to societal goods, like access to affordable food and energy, have been decreasing while exposures to harm have been increasing. The Russian invasion of Ukraine exposed vulnerabilities in European food and energy strategies, but rather than working to respond to protect citizens from exposure to harm, the European Commission’s lack of a proper risk management capacity made the situations far worse.

- German regulators pigheadedly shut down their last nuclear reactors at the same time as natural gas supplies were being sharply restricted due to the war in Ukraine. With high costs pushing a large percentage of German consumers into energy poverty, the best they could do is provide cash subsidies. The German decision to wind down their nuclear reactors wreaked of incompetence, bowing to the relentless pressure of a loud minority’s lies and fear-mongering while not managing the transition with any foresight, resulting in a long-term increase in coal-powered generation, CO2 emissions, poor air quality and increased energy poverty.

- As food prices sharply increased in 2022, the European Commission published a roadmap claiming that agriculture needs to be more resilient, recommending more organic and agroecological cultivation methods, seemingly ignorant of the potential yield losses from this politically-driven farming alternative. European chemical-political restrictions on agriculture, with no understanding of how their strategies were exposing farmers and consumers to serious vulnerabilities, led to the series of farmer protests in 2024.

- European countries did not manage the recent coronavirus pandemic well according to any competent risk management process. Societal goods were significantly curtailed while large portions of the public were left badly exposed to potential harms and vulnerabilities. It was tragic to see governments incapable of protecting their elderly from virus exposures while those least vulnerable were locked down and left to struggle with consequences from mental health to substance abuse to domestic violence. The innovative private sector and heroic healthcare public servants worked tirelessly to ensure goods while the confused policymakers consistently made the wrong choices for the wrong reasons.

In 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns, I wrote a seven-part series calling for a “Blueprint” for a future risk management process. This White Paper would be the first step. - The European Commission’s response to the threat of climate change, with its Green Deal strategy, was based not on protecting societal goods, but rather in cutting back human activities. Degrowth, deindustrialisation and decreasing living standards were the strategies, without any clear evidence these ideological impositions had a positive effect while societal goods were systematically restricted or eliminated.

In all of these cases, European leaders were guided, not by risk management principles but by their interpretation of the precautionary principle. While declarations of precaution are waved around the corridors of power in Brussels like some magic wand, it has never properly been defined or placed into a risk management strategy. Precaution has been identified as risk management, but it is merely a lazy surrogate for cowardly regulators.

It is time for the European Commission to articulate their risk management process. It is time for a White Paper on Risk Management.

Uncertainty vs Probability

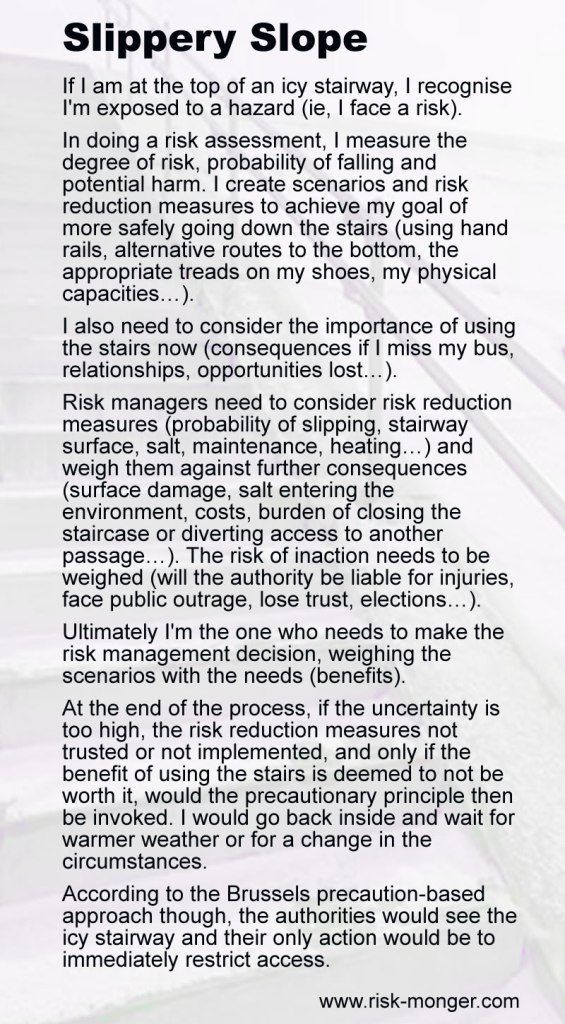

Precaution is what people naturally take when there is uncertainty and the benefits are not deemed essential. It does not come at the beginning of the risk management process but as a consequence of the failure to adequately manage risks. It is used when exposures to hazards are unable to be adequately reduced.

But the European Commission uses the David Gee/European Environment Agency definition of precaution which replaces the risk management process with a simple certainty checklist that reverses the burden of proof: only if an action, substance or product can be proven to be safe will it be allowed onto the market. This interpretation of precaution cleverly applies two relative, highly emotional concepts: safety and certainty, and bypasses the normal risk reduction process or assessment of the value of the benefits. Precaution is an uncertainty management tool, where removing uncertainties is the objective and any lost benefits are deemed unnecessary from the outset. If, for example, you cannot prove with certainty that a pesticide is safe (how safe and according to whom?), then under the precaution-based approach, it must be banned (with any benefits to farmers and consumers being sacrificed).

For European policymakers, this has provided the perfect opportunity to never be accountable for lost societal goods (“We are protecting the public and it is always better to be safe than sorry!”) while appearing to regulate. If there is a contentious issue with heated public debate (like nuclear energy, chemicals, GMOs or pesticides…) the regulator can pull out the precautionary passe-partout and tell the producers to come back when they are certain that the subject in question is safe, with certainty. And they can (and have) played this game for decades while societal benefits like affordable food and energy have suffered from the lack of regulatory support.

On pesticides, one can argue that there is uncertainty on whether the chemical residues on fruit and vegetables can cause illness, but the probability is very low. As Bruce Ames stated, decades ago, there are more rodent carcinogens at higher levels from the limited testing done on a few of the 1000 natural chemicals in a single cup of coffee than from the pesticide residues on a year of fruit and vegetable consumption. So while there is some uncertainty on the 100% safety of pesticide residues (thus justifying a precautionary ban of modern agricultural tools), the probability of harm (what risk managers need to measure) is so low as to be laughable. Where this policy pantomine becomes a tragic comedy is when the public, made afraid by the constant fear-mongering from activists paid by interest groups like the organic food lobby, cuts back on their consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables, elevating their risk of cancers. Europe is now importing more food than it is producing.

Risk Ignorance

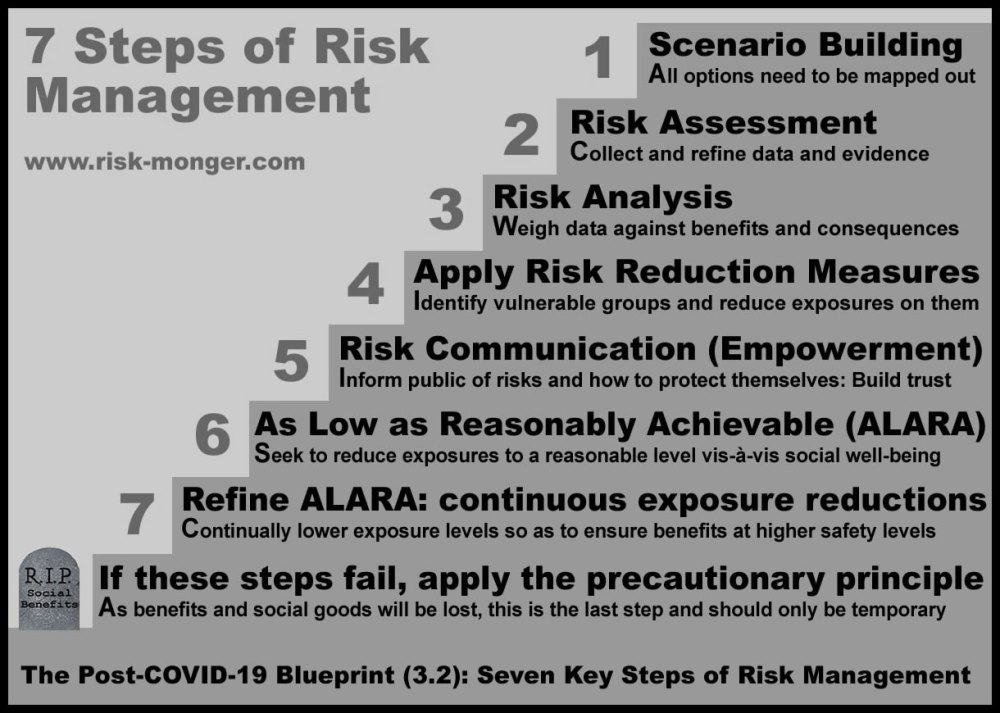

During the coronavirus pandemic, I was quite surprised to see how ignorant policymakers were about basic risk management steps. I wrote a series of articles to explain the RM process, culminating in what I referred to as the Seven Key Steps of Risk Management. For some policymakers though, I suspect the process was too much work or too politically risky when invoking the precautionary principle was more favoured.

For those cowardly policymakers, taking precaution is the easy solution, the consequences are usually not felt for a long period of time afterwards and no one would ever accuse you of making a mistake. So it is understandable how the precautionary principle has become a popular tool of first instance.

As “better safe than sorry” can never be considered as a wrong action (just usually not the best action), regulators are rarely judged for their failure to act. But there have been many disastrous consequences from this precautionary approach. During the Great Plague of London in 1665-66, the authorities, led by religious superstition, believed that cats were responsible for spreading the bubonic plague and, as a precautionary measure, tossed all of the cats into the Thames. This caused the rat population to explode and further spread the plague via the ticks that actually carried the disease.

COVID-19 was another case of the disaster of a precaution-based regulatory approach. Authorities had more than two months from the time the coronavirus was detected in China to the point where its containment was more difficult. In this period, the European authorities did not impose any risk reduction measures or implement means to protect the vulnerable populations. When the risks became too high, they simply then locked down most of Europe, cutting back on societal goods and imposing significant suffering from the restrictions imposed on their populations (without seeing any advantages compared to countries like Sweden that were less draconian on their populations). And even when researchers provided solutions like vaccines, a few cases of blood clotting following the AstraZeneca vaccine had officials like European Commissioner, Paolo Gentiloni, declaring the need to take precaution (fuelling public distrust and decline of use of that particular vaccine).

It is not a stretch to say that the European Commission does not understand or properly use risk management techniques and that their reliance on precaution has impoverished rational policymaking in Brussels. Following the COVID-19 debacle, there is an urgent need for a White Paper on Risk Management. But what would this analysis address?

What Would a White Paper on Risk Management Assess?

As the key concept for regulators, there are many aspects where guidelines on risk management are necessary. Risk management is a process from risk identification and scenario-building to risk reduction measures, and, if necessary, precaution. It should be broken down into the main elements in the risk management process where potential issues need assessment to provide guidance for policymakers.

What follows are ten elements in any risk management process that should be considered in detail in a European White Paper on Risk Management.

- Risk Identification: Risk identification is related to trust, or rather the lack of trust. So it is often socially defined, emotionally, outside of evidence or data. What one may identify as a risk that must be avoided, another may find inconsequential, especially in light of the benefits. Is it sufficient to identify gene-edited seeds as a risk because it took place in an industry-funded lab? Policymakers need to have a rational basis to filter through the public discourse on risks, levels of risk acceptance and values that amplify certain risks over others. Many risk issues are more value-based campaigns that should be assessed under different frameworks than the regulatory process.

- Risk Assessment: A risk assessment is meant to gather the important information necessary for the risk analysis process (including scientific data, impact assessments, scenarios, cost-benefit analyses and societal interests). Many debates on risk issues go back to what evidence is considered as valid or admissible in the risk assessment process. In the EU’s 2023 glyphosate reauthorisation process, the main challenge in the regulatory process was over whether the EFSA risk assessment had considered all of the evidence, the right evidence (ie, according to activists, EFSA had to exclude industry data) and other, non-scientific evidence. A White Paper on Risk Management needs to provide proper guidance on what type of evidence is valid for a risk assessment and whether the approach should be risk-based or hazard-based.

- Risk Reduction Strategies: Risk equals hazard times exposure. Often risk and hazard are confused (in some EU languages, they are the same word) and activists prefer to take the hazard-based regulatory approach where any low-dose exposure is reason to act. A White Paper on Risk Management needs to consider not only hazards, but what tools are in place, or should be in place to reduce exposure to these hazards and clearly distinguish hazards from risks.) If risk reduction measures need to be implemented, policymakers need guidance on how these measures should be imposed, evaluated and, at what point after a failure to comply or implement should precautionary measures then be applied.

- Acceptable / Achievable Risks: One important question is over how low of an exposure is acceptable. The key tool here is ALARA: As Low as Reasonably Achievable (also referred to as ALARP: As Low as Reasonably Practicable). The issue though is over what is ‘reasonable’. Should we have kept entire populations in complete lockdown until we could ensure they were 100% safe from a coronavirus? Is that reasonable? Is that achievable? Another example: the European Commission had worked for decades with European automakers on their voluntary commitment to reduce CO2 emissions. At a certain point it was clear they were not meeting their commitments to reduce climate and air pollution risks but there was no clear strategy on how to then enforce restrictive measures.

- Relative Risks and the Risk-Risk Paradigm: The Risk-Risk Paradigm is perhaps the biggest challenge in the risk management process. In addressing one risk, it is quite often the case that another, greater risk can arise. In acting to reduce pesticide use to promote public health, for example, policymakers could create a situation where the cost of fruit and vegetables increases to the point where people cannot afford healthy food, thus increasing cancer risks and other health vulnerabilities. Or regulations to curtail vaping and e-cigarettes could lead to increased tobacco smoking. All risks are relative and the European Commission needs to have a clear process to identify critical risks and consider the potential consequences of their risk management decisions.

- Impact Assessment Process: Often policy responses to risk situations can have even a greater negative effect than the actual risks. This was the thinking behind the Innovation Principle – that prior to any restrictive, precautionary decisions, policymakers need to examine what effect the decisions will have on the research community and their capacity to innovate and provide better, more sustainable technologies. To push the idea further, any risk reduction measures have to have their impact on societal goods and public benefits assessed. Following from the first part of this series, the White Paper will need to correct the flaws of the present EU impact assessment process.

- Risk Communications: A key for quantifying relative risks like toxic equivalences or probability of harm is a clear risk communications strategy. Most public risk aversions, from vaccine fear to rejection of emerging biotechnologies, come from poor communications and lost messages. We tend to want to blame disinformation campaigns, but if authorities were trusted, these fear campaigns and risk aversions would never be able to take root in the public narrative. A European White Paper on Risk Management will need to examine the decline in public trust in authorities and institutions and means to improve public engagement on risk decisions.

- Integrated Risk Management: The policy process tends to isolate (extract) the risk situation, and treat it apart from the entire system, which is integrated and interconnected. The food chain is a good example of how an integrated system from seed breeding to farm ecology to processing to consumers is important. The EU’s precautionary ban on neonicotinoid seed treatments isolated the systemic insecticide as a possible risk to bee health without considering the lack of alternatives, the effects on bees from increased foliar spraying applications, the reduced planting of important early-season flowering crops like oilseed rape further stressing pollinator health and nutrition. Extending the ban to non-flowering sugar beet and potato seeds left markets vulnerable to supply shortages and price increases, let alone limiting soil health with reduced crop rotation alternatives. Risks cannot be managed in a vacuum and the European Commission is aware of this. In Chapter 2 of the 2000 White Paper on Food Safety, the authors called for an integrated risk management approach to the food chain, but they never explained how to do that (leaving it to EFSA to eventually try to figure it out).

- Ex-post Analyses: Prior to any precautionary decision, risk reduction measures need to be applied and assessed. Europe has lost many innovative leads in biotechnology and chemical engineering because restrictions have been imposed before the researchers were allowed to manage the risks. Innovation is a process of continuous improvements, reiterations and refinements so before regulators come in with their restrictive, precautionary sticks, they need to set targets for risk reductions and analyse the progress. A White Paper on Risk Management would need to establish guidelines for how this progress will be assessed and communicated.

- The Place of Precaution: What is lacking in Europe today in a proper guidance document on where, when and how precaution is to be applied. The European Commission does not even have a clear definition of the precautionary principle (with their 2000 Communication being quite different from the European Environment Agency’s 2001 “Late Lessons” definition with scant references in the European treaties). As the precautionary principle is being misused and abused, to the detriment of European researchers, consumers and companies, this “convenient obscurity” has to be cleared up in the White Paper. As it is not a risk management concept, precaution should only be taken when the risk process has failed to reasonably protect individuals, wildlife or the environment.

There are of course some difficult concepts that will need to be considered that are not black or white. What is “reasonably achievable” for risk reduction levels? Should risk reductions be a continuous step process? How do different cultural attitudes to risk aversion affect the process? How should different types of scientists (chemists v biologists, virologists v epidemiologists) be considered (weighed) in the risk assessment process if their findings are so different? How can trust and engagement be developed around fear-laden, emotional issues related to public health and the environment? What role should interest groups play in the risk management process?

There is definitely a need for a European Commission White Paper on Risk Management.

A Risk Readiness Checklist

Given the importance of this White Paper’s influence on certain heated political issues and the likelihood of intense lobbying on external consultancies, this guidance document should be produced in-house rather than through a consultancy, best by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). Rather than simply producing a document that may or may not be read by regulators, the White Paper should produce a multi-step checklist to ensure that policies and the regulatory processes surrounding them are “risk ready”.

Perhaps the Regulatory Scrutiny Board launched in the Better Regulation package can be transformed into a Risk Oversight Board to ensure the risk management principles are strictly followed in any EU policy process. In a deeper dive into establishing a regulatory risk “blueprint”, following the badly botched EU COVID-19 governance failure, I proposed that each government department should have a Risk Management Unit to ensure that the best regulatory processes are respected.

I leave it to those far more competent than myself to pick up this responsibility in order to prepare a document to ensure that European policymakers have the necessary guidance to govern according to the highest regulatory standards.

Enjoyed this read (free with no ads)? Support The Risk-Monger via Patreon.

Become a Gold-Monger patron for 5 € / $ per month and get David’s newsletter.