French translation

There is a scene in the film Dumb and Dumber where Jim Carrey’s character, Lloyd, confronts the girl of his dreams wanting to know straight out what his chances were with her. When she replied that it was not good, maybe one in a million, he was absolutely elated. He had a chance.

This film was a precursor to the numerical illiteracy we face today in the Age of Stupid. One where people can at the same time accept a possible event that is highly unlikely while rejecting likely events due to the lack of absolute certainty. In other words, we have lost the capacity to measure, discern and distinguish probability from possibility (or what I would call having lost the capacity for reasonableness).

Some examples:

- If scientists cannot prove with absolute certainty that a chemical does not disrupt our endocrine system (perhaps in a low-dose exposure having a possible cocktail effect with other chemicals), then it must be considered as a potential endocrine disruptor (and banned). At the same time these chemophobes do not consider hormone replacement therapies, birth control pills, coffee, humus or soy beans as posing any endocrine risks (although the data is quite clear).

- Although the testing tools and labs are questionable, activists are finding extremely low residue traces of glyphosate in certain foods, and excluding the reality that it has a toxicity far lower than common ingredients found in cookies and chocolate, activists are successfully pushing to ban the herbicide. This will leave farmers having to use less benign alternatives and abandon sustainable soil management practices. This while the scientific community (excluding one conflicted agency) loudly declares its confidence in the health and safety of glyphosate.

- We drink copious amounts of alcohol, smoke and eat rich fatty foods (all known carcinogens), but I am regularly told that “consumers” panic at the thought of having exposures to a food additive, non-organic product or synthetic packaging (with negligible cancer risks).

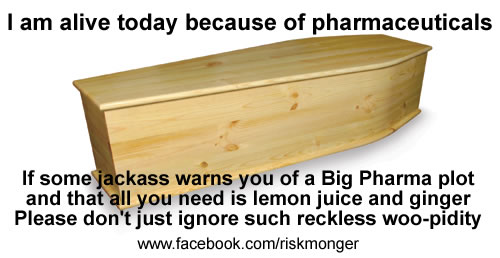

- The increasing success rates of cancer treatment, improving quality of life for survivors and better technologies have made “beating cancer” commonplace, but given that conventional treatments cannot offer patients complete life-long freedom from cancer (an impossibility even for healthy individuals), a growing number of cancer sufferers are opting for alternative, less invasive naturopathic treatment approaches like juicing (with no clear survival rate data available).

- While vaccines have eradicated diseases that used to wipe out significant populations and research is beginning to take a preventative approach to many common diseases (like cervical and breast cancers), an alarming number of parents have forsaken all vaccines. Why? There is a remote possibility, highly amplified, of adverse effects from vaccines which strong reassurances from the authorities only seems to stoke further.

- Research has found a means to reduce pesticides sprayed on leaves and soil by treating the seeds at planting, reducing risks to the environment and humans. Because it is impossible to prove with certainty that there is no risk to pollinators (eg, with neonicotinoids), there is a high likelihood that all seed-treated systemic pesticides will be banned (also for non-flowering crops like sugar beets). Farmers will have to resort to spraying with older, less efficient technologies that we know harm bees. Research funding on the known causes of bee decline (viruses and parasites) are drying up and farmers are planting less pollen-rich crops following the EU neonic ban.

There are many decision theories assessing such “justified illogic” perceptions (which I won’t have space to get into here), but this irrational naturopathic narrative is driving a worrisome body-blow into the ability of risk managers to process and think scientifically. It seems as if people leading environmental-health debates no longer have the capacity to distinguish remote possibility from high probability. In the quest for the certainty management of hazards (demanding the impossibility of an exposure to a hazard), activists no longer factor in probability of adverse effects, just the possibility that something may go wrong. And if a hazard is possible (Lloyd’s one in a million), then the hazard must be removed.

We need a word for this irrational phenomenom.

Possibilism

Until now, I have referred to this lack of reasonableness as “The Age of Stupid” but I recognise that some educated people fall for this justified illogic. I would like to coin the term: “Possibilist” to refer to a person who accepts a remote possibility as good reason to avoid a decision and take precaution. Possibilism allows those who are “trust challenged” to reject a technology, substance or hazard if it is not possible to declare with certainty that it is safe (keeping in mind that one can adopt a very high normative standard for safety).

If it is possible for something to cause harm (a pesticide, vaccine, food additive…), a possibilist will reject reassurances from authorities and scientific experts and demand that action be taken to protect them and remove the hazard. A possibilist does not trust science or authorities – they trust other possibilists they have found on the Internet in their quest for self-education and create their own data, science and theories. Traditional science is seen to be industry-driven and flat out rejected while they promote the science of their gurus, shamans and opportunists.

A possibilist is an idealist driven by a passion to promote some perfect world (natural, free from synthetic interventions or corporate models) that is held in contrast to the evils that human intervention have to date inflicted on society. I often highlight neo-Malthusians who feel that the world cannot sustain large populations and man’s interventions have only led us further down the path of impending catastrophe. Negative consequences of their dogmatic fundamentalism are played down or considered as necessary (global food insecurity, increased diseases, …) to right the wrongs of the man’s endeavours to solve the problems and challenges humanity faces.

“If you love your family and friends, please share this message!”

How to piss off the Risk-Monger

Possibilists are usually smug, elitist chemophobes enjoying the luxury of a world with alternatives (affording an abundant access to food, the benefits of a widely immunised community and medical technologies that can correct bad decisions). They form communities (social media tribes) that make remote possibilities feel like high probabilities and regulatory safety reassurances appear doubtful and conflicted. Possibilists can afford to make decisions demanding 100% “safety” (they have money and are likely not suffering from any life-threatening disease), but what happens when they impose these expectations on others?

People in developing countries don’t have the luxury of listening to the possibilist nonsense, nor do the poor or ill in advanced economies. People with empty bellies, life-threatening diseases or limited means make decisions according to the best probable outcome (with the least loss of benefits or quality of life). When you are struggling to feed your family, you are not concerned about whether your bloody organic beef was grass-fed, you trust authorities and look for any protein source you can afford.

People in developing countries don’t have the luxury of listening to the possibilist nonsense, nor do the poor or ill in advanced economies. People with empty bellies, life-threatening diseases or limited means make decisions according to the best probable outcome (with the least loss of benefits or quality of life). When you are struggling to feed your family, you are not concerned about whether your bloody organic beef was grass-fed, you trust authorities and look for any protein source you can afford.

And this is where the Risk-Monger gets pissed off. If possibilists were simply to stay sheltered within the confines of their cultist encampments sharing their chemophobic Kool-Aid only among themselves, then the rest of us could ignore these privileged, uneducated idiots and get on with developing technologies and systems that benefit humanity. But led by their Gurus of Ignorance, possibilists are Ludditiously expanding their influence via emerging on-line communication tools that exploit the vulnerable and attempt to rationalise the ridiculous.

Presenting themselves as the maligned majority, the voice of the people, the 99%, the “Us” versus some evil, industrial, globalised “Them”, possibilists have “lobbied up”, raised funds, networks and media tools and have now entered the policy ring. Lobbying is not about improving humanity; it is not about telling the truth; it is not about saving the environment … rather lobbying is about winning. What I find today is that we are trapped in a myriad of irrational policy tools imposed on the Brussels lobby arena by clever, cunning possibilists who have wormed their way into European directorates and agencies. They are using these tools to create conditions where reason, science and evidence are isolated and restricted by fear, vulnerability and populism.

This would be fine if possibilist policy were simply to stay sheltered within the confines of the rich, elitist Brussels Bubble, largely ignored by Member States and the rest of the world. But many developing countries, without sophisticated regulatory structures are simply adopting EU regulations and standards en masse, attracted (or threatened) by trade prospects. Emerging economies cannot afford to impose such possibilist policy measures on their populations.

Last year I met agricultural experts in South-East Asia. Countries like Thailand and Indonesia are merely adopting EU pesticide regulations as their own. Indonesia, for example, has 33 million smallholders (add children and spouses, and that is around half of the country’s population) each farming around a hectare of land or less. If they lose a crop, they miss the rent and leave the land. The EU’s “designed for failure” pesticide policy was not intended to be adopted by small-holder driven countries without Common Agricultural Policies or any money to pay farmers when they inevitable fail to produce yields without agri-tech. This reality should make European policy-makers think twice about listening to stupid people spreading possibilist nonsense around Brussels. Perhaps European civil servants should become more responsible.

To pour fuel on the fire of this outrageous stupidity, given we are no longer able to feed themselves, Europeans then impose obligations on developing countries to re-appropriate their agriculture to accommodate hungry western bellies (who out of possibilist puritanism demand organic food) rather than developing an agricultural policy for their own economies. This luxury foodie demand puts pressure on small-holder family farms (and their children).

All of this possibilist madness is conducted within a sanctimonious narrative that they are saving the world from the evil industry-led science that is intentionally poisoning babies and polluting the planet for greed and power. Possibilists believe they are occupying the moral high-ground, turning their smug self-satisfying eco-religion led by fundamentalist zealots and manipulative preachers into congregations of passionate militants.

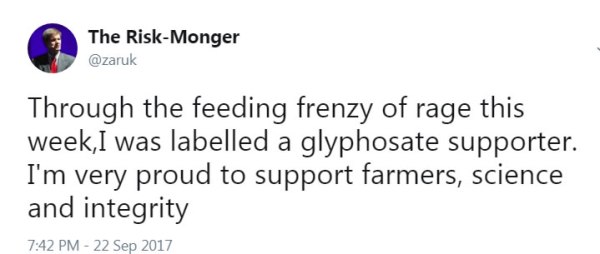

Not a day goes by where I am not personally attacked by people convinced I represent evil. Last week a Brussels news outlet labelled me a, gulp, “glyphosate supporter”. The journalist admitted she was wrong, but that is no reason to correct it. I suppose there is something purely evil about supporting farming and science so who cares? Farmers, professors, researchers are attacked on a daily basis until most give up, become discredited or find other occupations. This is the first step in how they are winning – denial of dialogue, facts and evidence. A hollow victory for the integrity-challenged leaving the world a more ignorant place.

Not a day goes by where I am not personally attacked by people convinced I represent evil. Last week a Brussels news outlet labelled me a, gulp, “glyphosate supporter”. The journalist admitted she was wrong, but that is no reason to correct it. I suppose there is something purely evil about supporting farming and science so who cares? Farmers, professors, researchers are attacked on a daily basis until most give up, become discredited or find other occupations. This is the first step in how they are winning – denial of dialogue, facts and evidence. A hollow victory for the integrity-challenged leaving the world a more ignorant place.

I think the Risk-Monger has a right to be pissed off!

The rest of this blog looks at how the perverse possibilist policy tools have led to a hazard-based approach in Brussels and is responsible for the precautionary paralysis we are suffering today.

Paracelsus was a medieval alchemist

Paracelsus stated in the 16th century that “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” One aspirin can do wonders for a headache, but one hundred may not be so good. This probability of harm principle has served toxicology, risk management and humanity very well (until the ‘more sophisticated’ possibilists came along and decided to correct what had failed to deliver certainty). Today possibilists cite the possibility of long-term low-dose exposure (eg, of glyphosate, bisphenol A or, well, anything), possibly combined with other unknown chemicals as grounds to reject any discussions of acceptable dose or risk.

All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.

Some medieval alchemist

Chemophobic possibilists get stuck on the first part of the Paracelsus Principle: poisons are unwanted and must be avoided.

So NGOs will do blood or urine tests on the “walking wounded” – the victims of science and technology – find evidence of the presence of a chemical that nature had not bestowed upon us, often in the part per billion range, and declare the poison as a threat that must regulated (ie, banned). That the levels of exposure are so low as to not in any way be harmful (the dose makes the poison) is not to be considered. And if a scientist, regulator or communicator has the gumption to even consider raising this point, well, the possibilists are prepared.

In 2005, while handling communications at Cefic for Product Stewardship during the European Parliament’s first reading of REACH, I had tried to introduce reason and Paracelsus into the discussion. David Gee from the European Environment Agency (on loan from his leadership of Friends of the Earth UK) declared that we must no longer consider that the dose makes the poison (he even referred to Paracelsus as a “medieval alchemist”), but rather, that the “timing makes the poison”.

Levels of acceptable dose had to be adjusted to meet possible chemical exposure of children, infants and foetuses (and there we would find no acceptable dose levels). NGOs were testing umbilical cords and breast milk with sophisticated (and very expensive) biomonitoring tools, looking for shadows of chemical exposure, job-site listings were seeking eight-month pregnant women for short-term engagement at activist campaign events … in short, at the time of REACH it was open season on Paracelsus.

The Possibilist Principle

During REACH I found myself, for the first time, in the bizarre world of possibilism and identified what I would like to now call the Possibilist Principle. The mysterious long-term low-dose effect made it impossible to conclude that “risk = hazard X exposure”. Any level of exposure was a hazard, thus any hazard was a risk. And even if toxicologists could show how a foetus could survive industry’s evil chemical onslaught on humanity, the possibilists had another card to play.

If a chemical were not particularly toxic or the long-term dose were tiny, we still could raise the possibility of a cocktail effect. That one synthetic chemical (that did not come from nature) could, even at the lowest levels, react with another chemical in a way that we, well, just did not know, and in this man-made toxic soup, lead to all sorts of problems (cancer, obesity, endocrine disruption, allergies, autism … the possible list is endless). With the possibility of cocktail effects came a fait accompli – the Paracelsus Principle was dead – long live the Possibilist Priniciple.

It did not matter that the average meal combines around 10,000 chemicals (in ways we know very little about), because, well, there was that one synthetic chemical introduced into the world that could have a higher possibility of wreaking havoc on humanity. Sure!

The Possibilist Principle allows activists to impose regulatory roadblocks on any technology or chemical they don’t want by raising three unlimited tools of possible harm: the possibility of long-term low-dose exposure, the possibility of an unknown cocktail effect of combined chemicals and the possibility of harming vulnerable populations at levels we know so little about. The possibilist ignores benefits or societal goods, promotes a naturopathic lifestyle and entails a precautionary, hazard-based logic (more on this shortly).

Personal note to this story: When the REACH process had ended, an exhausted Risk-Monger had thought the high levels of Stupid permeating the Brussels conference centres would have stopped, but then came the revision of the Pesticides Directive and then came the endocrine activists’ “there is so much we just don’t know” obfuscation … the opportunities were endless! This continuation of selective banning of chemicals (the activists had drawn up an attack list) had become a full-time profession. The Possibilist Principle was well enshrined in EU environmental-health risk policy. I decided then to retire rather to spend my time dealing with such manipulative morons.

Possibilism and the Hazard-based Approach to Policy

Possibilism and the use of the debilitating Possibilist Principle tools (long-term low-dose exposure coupled with unknown potential cocktail effects) were not developed by stupid people believing in a world without chemicals. Hardly. These activists were cunning and spiteful, driven by the obsession to win and impose their radical, anti-industry, anti-trade myopia on the world. They were funded by industries (from Big Organic to Opaque Aluminium) who have profited well from these campaigns. Kudos to them, they made the rest of us look incredibly stupid!

The hazard-based approach to policy follows inevitably from the Possibilist Principle. This approach is not risk management but is intended to undermine the risk management regulatory process and that dastardly Paracelsus. Traditionally regulatory policy was approached via risk management. When a risk is identified (a hazard we are exposed to), the regulator or risk manager has to find a way to limit exposure to such hazards. This may entail putting a hand-rail next to steps, erecting a stop-light, ensuring that building codes can withstand earthquakes, reducing air emissions on automobiles or replacing products with less harmful ones.

Risk management is governed by ALARA – to reduce exposure to as low as reasonably achievable. What is considered reasonable depends on the benefits, cultural traditions and societal risk tolerance. See my Risk School series on the difference between risk-based and hazard-based approaches to policy and further illustrations of how ALARA is applied.

When possibilists put any level of exposure into question (any level of exposure could possibly harm some people), then regulators have to equate risk and hazard, and if there is a hazard identified, or if we are in any way uncertain of the safety of a product, substance or technology, then the risk manager must remove it.

If the hazard-based Possibilist Principle were to be applied with consistency, then wouldn’t every technology, substance or man-made/natural product be banned? Possibilists are indeed trying to ban all synthetic pesticides and chemicals, many want vaccinations to stop and some feel all pharmaceutical interventions (outside of homeopathy) should be regulated out of existence. However, possibilists are smart enough not to touch widely appreciated benefits like mobile phones, cars and meat. They also would never dream of imposing the Possibilist Principle on pesticides approved for organic farming (which would lead to all of them also being banned). Nobody claimed that possibilists were not hypocrites!

A hazard-based approach to regulations follows almost inevitably from applying the Possibilist Principle. And from the hazard-based approach comes, once again almost inevitably, the regulatory reliance on the precautionary principle. Therein lies the logic of illogic.

Precaution is a normal emotion … not a normal policy tool

The Possibilist Pope, David Gee, identified the best means to disrupt western regulatory policy: redefine the risk assessment process with proof of safety (a demand for certainty of a normative emotional concept) at the heart. Gee’s Late Lessons from Early Warnings (volume 1) redefined the precautionary principle as the reversal of the burden of proof. Rather than regulators proving something is hazardous (ie, identifying a risk and managing it), Gee, campaigning from his post in the European Environment Agency, demanded that industry had to prove that something is safe before it could be authorised on European markets.

This was an absolutely brilliant bastardisation of traditional regulatory policy-making as it introduced emotion and subjectivity into what had been a rational scientific process – creating the “Pathway to Possibilism“. Gee’s demand for precaution was a demand for certainty at the gate – no certainty, no entry onto a market (this was the basis for REACH: “No data, no market”). But what can science be 100% certain about? David Hume recognised the limits of empiricism several centuries earlier – he showed how we could not be certain that even the rules of gravity could apply in future. This gave activists the licence to lie and raise doubts about products and substances they did not like.

Gee’s Possibilist Precaution also created a demand for safety – a second emotionally loaded concept. What I deem as safe or as an acceptable risk may not be shared by the trust-challenged person beside me. So even if scientists may prove a product safe, David Gee could simply shrug his shoulders and mutter that it is not safe enough. For possibilists, even a remote possibility of harm is deemed therefore not safe enough … sorry industry, but no market for your beneficial drug, chemical or substance. Six years ago, I presented seven reasons why we should abandon this perverse version of precaution.

Of course, it was very difficult to demand a certainty of safety within the traditional scientific methodology and David Gee knew that. Volume II of his Late Lessons was a failed attempt to introduce another tool – redefining science according to an emerging, relativistic approach called “post-normal science”. Gee was in touch with a school of philosophy of science thinkers, mostly sociologists congregating in Norway, who feel that science should not be left to the pure scientists. Heaven forbid!

The risk assessment process, these renegades argue, should be opened up to public concerns and societal inputs. For example, the science on GMOs is clear – it is safe and meets all the regulatory demands to be allowed onto the European market. But post-normal scientists would say, once again: “Uh-Uh, not good enough! The public wants another type of certainty.” We see post-normal scientists active in the neonicotinoid debate (with activists like Gérard Arnold and Jeroen van der Sluis publishing articles on how to fix the “broken” risk assessment process), while Christopher Portier has also taken on the task of undermining the glyphosate risk assessment process.

If you approach uncertainty management from the societal perspective (ban whatever does not meet societal demands for certainty) rather than the scientific one (continuous improvement and scientific development), then your definition of the role of science in the policy process is no doubt going to change. So Gee concluded, in Late Lessons II, that the role of (his new definition of) science should be to focus on correcting all of the mistakes that science and technology have made in the past 500 years (rather than discovery, development and problem solving). In other words, throwing out everything that does not meet the post-normal demand for safety and certainty. That is pretty well every technology these neo-Luddites don’t like (most, but not all of them being related to technologies developed by industry … Hmmm, I see a trend here!).

Babes in Post-Modernist Bathwaters

Marcel Kuntz, a French biotech researcher, has written several excellent articles linking the recent rejection of scientific research and technology to a post-modernist belief that, as science cannot prove anything with certainty, therefore nothing can be known. And if nothing can be known, then our scientists today have no credibility. For example, if a scientific theory is built on a paradigm and that paradigm, as Thomas Kuhn argued, were to shift, leading to a scientific revolution, then no scientific theory can be trusted. It would not pass the muster demanded by certainty sharks like the post-normal possibilists.

So knowledge, built over centuries of scientific work, is now subject to participatory buy-in from stakeholders without any interest, expertise or, frankly, intellect (sorry Marcel, my crude addition). Years ahead of the curve, Kuntz essentially defined a world governed by alternative facts and post-normal sociologists.

How did these possibilists get to such a confused state?

I think we have to go back several centuries to Immanuel Kant. Kant was the first German philosopher to write in German rather than Latin and he often played with words that had multiple meanings. One such example was the word “objective”. For Kant, objective had two meanings (and addended with two different Latin words):

Objective can mean absolute and universal (similar to the Platonic forms). This is the type of certainty mathematicians and Cartesians crave.

Objective can also mean “not subjective”. If I say “My wife is beautiful”, that is a subjective statement. If, however, I find ten or twenty individuals who agree with me, it becomes objective.

The “objective” demanded by the possibilists is that we have to be absolutely certain (first sense). Science though is built on Kant’s “not subjective” approach – that we continue to test our theories, refine them and strengthen our understanding. The more tests failing to falsify a theory, the more objective it becomes.

Science is not about Cartesian certainty, but about advancing the body of knowledge. What possibilists are doing is putting a confused demand of certainty on science, willing to throw out the entire body of knowledge should their emotional needs not be met. This is madness.

That almost all of Brussels has embraced this illogic shows how intellectually barren the Bubble has become. Maybe I should not have retired ten years ago!

*******

Going back to our possibilist hero, Lloyd, in Jim Carrey’s Dumb and Dumber, we have to accept that we cannot teach possibilists to be numerically literate or to even be reasonable – they are not interested in facts, data or evidence – they have an agenda they are hell-bent on imposing on others.

I thought of Dumb and Dumber while watching the recent GMOs Revealed lobbumentary. In one episode, anti-GMO, anti-vaxx advocate, Toni Bark, in an interview with Robert Saik, was searching for a means to conclude that glyphosate did cause cancer. Her logic was that if it were not 100% certain that glyphosate did not cause cancer, then it likely did. Poor Robert didn’t speak her Lloyd-like logic.

I now have a word for this. If only I can find an antidote!

Hi Did you read Aron Blairs deposition? I an trying to dig a little deeper and came across USRTK critisizing the Reuters story. But I dont know what to make of this organisation and og theory natrative is biased. Can you help? Best regards Claus

Sendt fra min iPhone

> Den 3. okt. 2017 kl. 00.11 skrev The Risk-Monger : > > >

LikeLike

I was shocked at many of his comments in the deposition, calling it the Blair-IARC Papers. Here are some memes I had done for my twitter page:

1. On how an organic industry lobbyist, Carey Gillam, was working closely with Blair and Portier – the activist science who colluded with IARC’s monograph team: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DCnsFBBXoAAfZbn.jpg

2. That Blair was consulted by activists about the Monsanto Tribunal: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DCyG4K2WAAAV9fr.jpg

3. How Blair was working with NGOs that IARC referred to him: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DCzxeqhXsAA1Eis.jpg:large

Sadly, I do not have the lobbying capacity compared to the Organic industry in the US, so I could not take these points and hammer the hell out of them in the media. Compared to the marketing and lobbying machinery of Big Organic, the rest of us are mere amateurs. At least we have scientific facts on our side!

LikeLike